There, at the foot of my driveway, came an unexpected moment of peace. Drifts from the seemingly endless winds had edged the blowing snow over the rise and into the lip of our south prairie in near parallels, forming a fan-like array. I was en route to the mailbox as the sun was lowering into a sunset. Fortunately I had my camera along. A quick single paragraph back story:

Moments before I had looked through the plateglas window of our kitchen when I noticed odd poetic lines crossing a smooth expanse of snow. A “blue hour” color tinted the snow. At the moment and the distance it was difficult to see what might have created the burrowing lines, so I quickly dressed for the elements and grabbed my camera. Closer to the two inch depths of the lines were literally thousands of tiny paw prints. Voles were my assumption. Just beyond the half tunneled lines were telltale rabbit prints, which were enormous compared to those inside the small crevices. It was moments later that I came upon that unexpected moment of peace.

It was impressionist artist Henri Mattisse who noted that “a certain blue enters your soul.”

Was that my “certain blue?” This was late afternoon mere hours after the brutal murder of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis, the second of two ICE murders and the third resident ICE had shot. Renee Good’s murder, and the short film of her comment to her killer seconds before she was murdered, was challenging enough for my son had lived for a few years within a block of her murder. Pretti’s murder two weeks later hit me almost in the same manner as the second plane crashing into the World Trade Center. This time the attack against our nation was from within, perpetuated by our own president and his minions. After plodding through a trying day of distress came this unexpected sense of calm.

As this wave momentarily washed over me my breathing was easier. That cloud of discontent and anger was slightly lifted. Bluish colors eased from the images an hour of so later when I brought them up on my computer along with various shades of violets streaking through. Although I had driven and or walked past those drifts a few times before, there was hardly a reaction. Which made me wonder if the colors could have possibly created such a near instant sense of calmness?

A study by the Moffit Cancer Center found that colors can affect your subconscious, and the color blue is strongly associated with peace, calm, and tranquility, evoking feelings of serenity, stability, and relaxation. Shades of violet, or purple, adds the Center, can evoke spirituality and inner balance. Perhaps that might explain the psychological finger-snap of calmness I had felt.

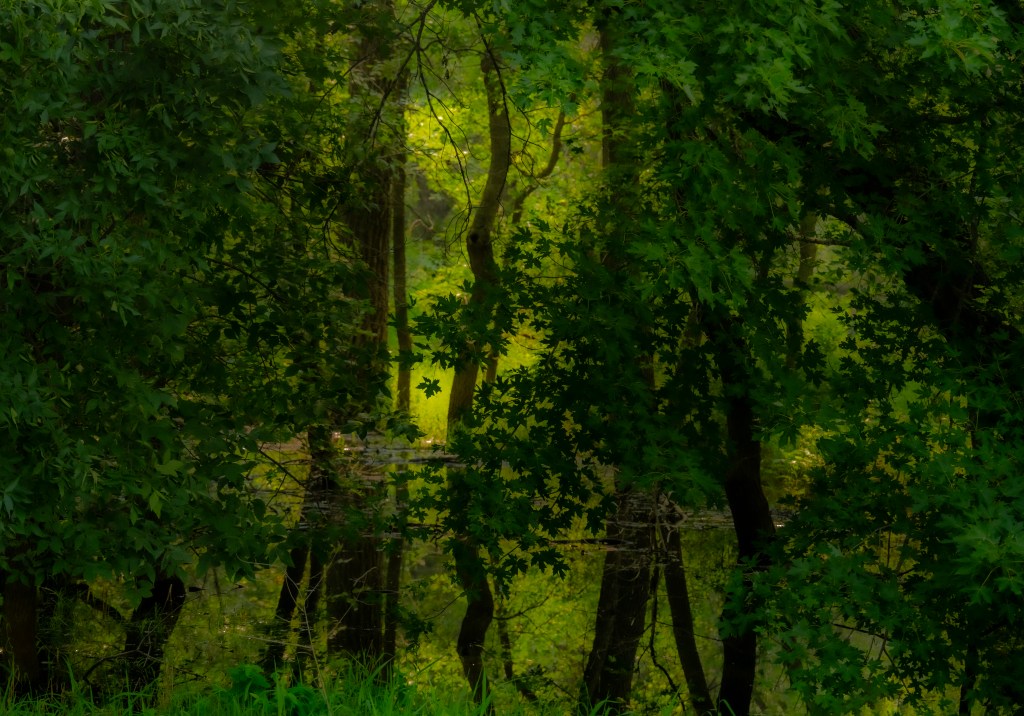

Other colors the Center says may have a similar impact: Green represents nature and offers a calmness and restfulness, while lighter shades like soft pink may promote physical soothing, and even white symbolizes peace through symbols like a dove. Snow and ice perhaps isn’t quite as soothing and comforting as, say, Richard Bach’s “Jonathan Livingston Seagull.”

According to their website, yoga mat company, Manduka, did numerous studies on the affects of color as they searched for hues they felt would create a more mellowing mood for practitioners, and blue was among their favored colors.

Enough of science. How does this fit into the spectrum of the arts? After looking at the colorful blue and purplish sunset colors amplified by the wind waves at the base of our driveway, a quick review was made of some of the earlier images that had affected me at some point. One example was a Winter Solstice image taken last December. Although I had visualized a different image, a walk to the river’s edge allowed me to find a slight hint of yellowish light in the midst of a jagged ice floe bathed in a soft blue. That yellow seemed to symbolize an emergence of resistance in the depths of the blueish ice — this was barely a week after ICE had landed in Minneapolis, and only a few weeks before their two murders. Within the comfort of blue the yellow seemed a beacon of hope.

Impressionist Claude Monet described such a sensation as a “colorful silence,” while Ralph Waldo Emerson noted, “Nature always wears the colors of the spirit” while capturing the serene, grounding influence of softened hues.

As I look around in these dour and dangerous times, there seems a need to find a some sense of inner peace and comfort. Moments in nature are offered as a way as do colors. Mine momentarily came in remnant colors of a sunset on a cold winter afternoon at the foot of our driveway. And a day or so later, walking along the edge of the prairie as evening settled in came another moment of calm that is much more common, that of what a young friend once labeled as a “rainbow” sky — those “twilight hues” of softened blues that meld into a soft violet along the prairie horizon as darkness settles in. I have a deep longing for such moments.

Long ago my eyes were drawn to the eastern sky more so than a setting sun, seeking those ambient and softened colors along the horizon, those same twilight colors I remember from my teenage years while casting flies close to the cattails of a farm pond and feeling the coolness of the evening surround me. That softened violet that yields ever so slightly to a milky blueness, of how those pastel colors of an approaching evening would slowly ebb away the cares of the day. Yes, Monet’s “colorful silence.”

Unless we are blanketed with deep cloud cover, the beauty of ambient colors banking off distant clouds in easterly skies have captured me for decades. Then there are those rare moments of being unexpectedly surprised by the soft blues and purples in wind blown snowy drifts that offers a sudden calmness in the midst of our nation’s turmoil. In these changing times. In these times when a hint of “colorful silence” seems a blessing.