We are living in desperate times, a time when for all practical thoughts and visions our nation is reliving the Nazi takeover of pre-war Germany of the 1930s. Times when a political party and their leader has provoked not only a possible war against another country, but also seems intent on starting one on our own soil. The murder of a young Minneapolis mother, 37 year old Renee Nicole Good, by our president’s “storm troopers” in a South Minneapolis neighborhood feels like a tipping point.

A few hours later ICE storm troopers raided Roosevelt High School shortly after the nearby murder prompting Minneapolis Public Schools to cancel classes district-wide for the remainder of the week “due to safety concerns.” The district stated it was acting “out of an abundance of caution.” In an American city.

Have we had enough? Protesters filled the neighborhood where she was killed, within a half block of where my son lived 16 years ago before moving to Norway, then as darkness settled over the city, thousands packed downtown Minneapolis’ 3rd Street from city center all the way down several blocks to the Viking’s stadium. The noise of protest was loud and crystal clear — get Donald Trump and Kristi Noem’s ICE out of Minnesota!

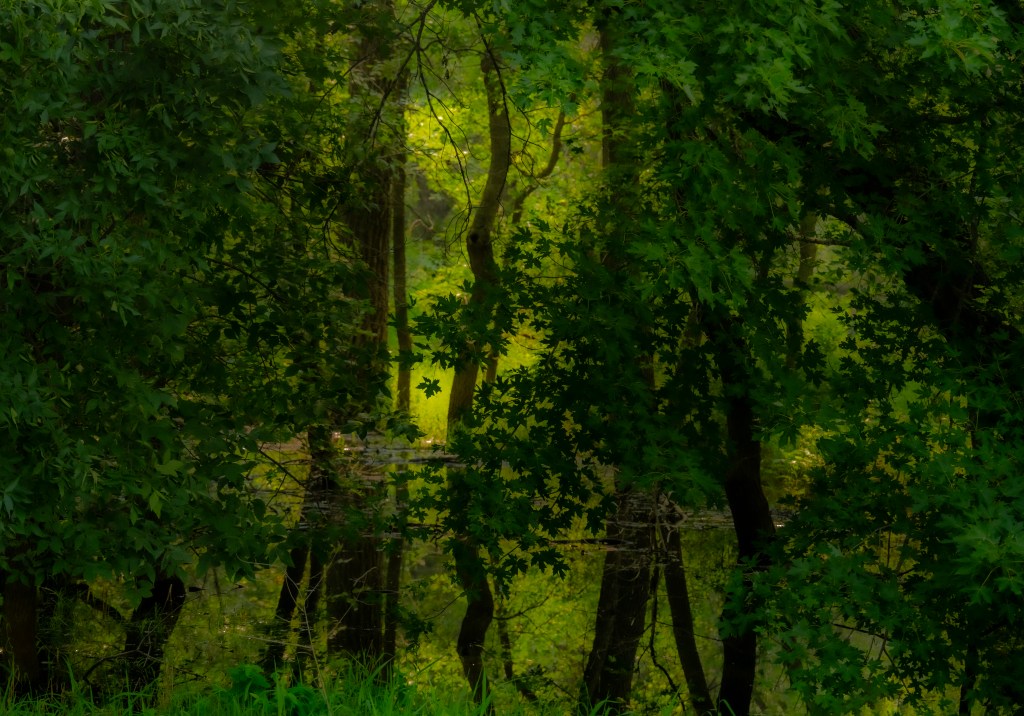

A year ago November, the morning after the election when Trump was declared the winner, I left home in my pickup with a need to simply be alone, to seek calm waters. About five miles from here I passed a wetland where I simply had to stop to gaze at the waters. Calm waters. Over the years there was seldom a time when there wasn’t a wind-swept surface, yet on this moment there was barely a wave. A slight breeze riffled a tiny portion across the way as I raised my camera for a picture, an image that has twice been selected as a viewer’s choice in exhibits. That wetland moment was the just the beginning of my quest. Several more prairie wetlands were visited, ones I routinely visit for my art, and on each the waters were calm. Was this an omen? That was my hope. Since the inauguration our lives nationwide have been altered and chaos reigns.

Nowadays my thoughts are to look for guidance from a poet like Mary Oliver, or from a philosopher like Wendell Berry, someone who can offer solace in such troubling times. Or perhaps even Renee Nicole Good, considered a notable poet in her own right. After her thoroughly unnecessary murder by ICE goons, the mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey, in a press conference in the midst of his dismay, shouted for ICE to “get the fuck out of Minneapolis.” A few hours later Governor Tim Walz said he was putting the Minnesota National Guard on alert. Two courageous leaders were standing in defiance of our unglued president, his ass-sucking Congress and Supreme Court, his storm troopers, ICE, and their “Barbie”-like leader, Noem. Will his own party finally take a stand of defiance? As of now, apparently not.

In my reckoning of the election 14 months ago, my expectation were that we would again face uncertain times, much like we faced in his first four year term that ended with an assault on our nation’s capital on January 6, which interestingly enough was a mere five years and a day before the murder of the young mother in Minneapolis. My fears 14 months ago were overshot within weeks of his new administration and is decidedly worse. We awake each morning wondering, “What next? What new horrors will we awake to?”

Our humane and human safeguards environmentally and health wise have been basically trashed. Vital research has been gutted with layoffs and firings. Basic human rights are seemingly long gone as bigotry becomes wholeheartedly welcomed by his followers and such presidential advisors as Steven Miller. International markets for our farmer’s crops have been destroyed, as have safeguards for our lonely planet.

We have a cabinet and presidential advisors who are either incompetent or are Nazi sympathizers with a published (Project 2025) goal to destroy our government. Our allies, including our neighboring nations to the north and south, have been sullied. Our allies across the Atlantic have wholeheartedly dismissed us as a powerful and friendly nation. NATO has been scoffed at by his administration and the once proud Republican Party.

His “make America great again” is long past the joking stage. This past week he rose past even Putin to capture another nation’s president and his wife in a midnight bedroom raid and taken over the oil reserves. Does this set precedent of disregard to international (and even our own Constitution) law, to open the doors for Putin to kidnap Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine, North Korea’s Kim Jong Un to grab his South Korean counterpart, Lee Jae Myung, or even China’s Xi Jinping to raid the bedroom of Taiwan’s Lai Ching-te? Trump’s lawlessness apparently has no bounds and is a threat to not only us in Minnesota, but to humans worldwide.

Those peaceful times, and the calm waters that soothed my anxiety and fears mere months ago are now deep in ice (lower case!). If Good’s murder is indeed the tipping point, what next? Leave the country? I have a son with disabilities including autism living in a group home, which our current health care czar dismisses as a sham. I cannot abandon my son. And now my other son, who married a Norwegian woman and has built a wonderful life in Norway, just messaged me that he has decided to renounce his U.S. citizenship over this murder in his former neighborhood, on streets where we have walked together as father and son in search of a good immigrant-owned restaurant. This one hit my heart nearly as hard as watching the endless reports on the ICE murder.

My sincere hope is that justice will be served for the murder of Renee Good, that Congress will finally step up to oust Trump and his so called cabinet, and that the threats against our neighbors be they other nations, our immigrants and even our own communities will cease. My desire is to see Trump, Noem and the alleged shooter, identified as Jonathon Ross, imprisoned. Perhaps that will be the light “in the midst of darkness” as Gandhi once suggested.

Then I read these words from a post by dear friend and naturalist Nicole Zimpel, an incredible human and nature artist who years ago went into the woods to rediscover her soul: “I am angry because of the brazen and lawless actions of this administration. But, I refuse to be guided by this anger. I’m just trying to work through it as best I can. I am deeply sad about the division amongst people in this country, and I’m working through this too, but what I have found is that the best way to counter my own sadness is to do something good or helpful to others and to my surroundings. It’s little, maybe even insignificant in the larger picture, but I do it anyway.”

Nicole is the “ultimate” optimist who has an innate ability to rise above the darknesses faced in her life, a woman I hold dear as I do the words of Oliver, Berry and Gandhi. She’s a good role model, for I, too, have a lot of anger about what has happened and is now happening to our nation and state. May you find a moment of peace in the images I now share as a bouquet along with a memorial for a government sanctioned murder of a young mother, images of prairie flowers that I have garnered in my moments of uncertainty. Images for the late Renee Good. To paraphrase my friend, Nicole: “It’s little, maybe even insignificant in the larger picture, but I’ll do it anyway.”