As a sawmill guy, wood artist Doug Pederson perhaps felt a tinge of financial joy whenever he saw me saunter through the door of his “Doug Cave” studio on the hill above Montevideo. He and other sawmill guys, and even the floor help at those box store lumberyard joints like Menards, might have sighed in relief. I’m the fellow who painstakingly looks through an entire stack of lumber before happily walking out with a board or plank that no one else would ever consider buying, character boards with odd knots and groovy grain, nicks and knocks and varying natural colors.

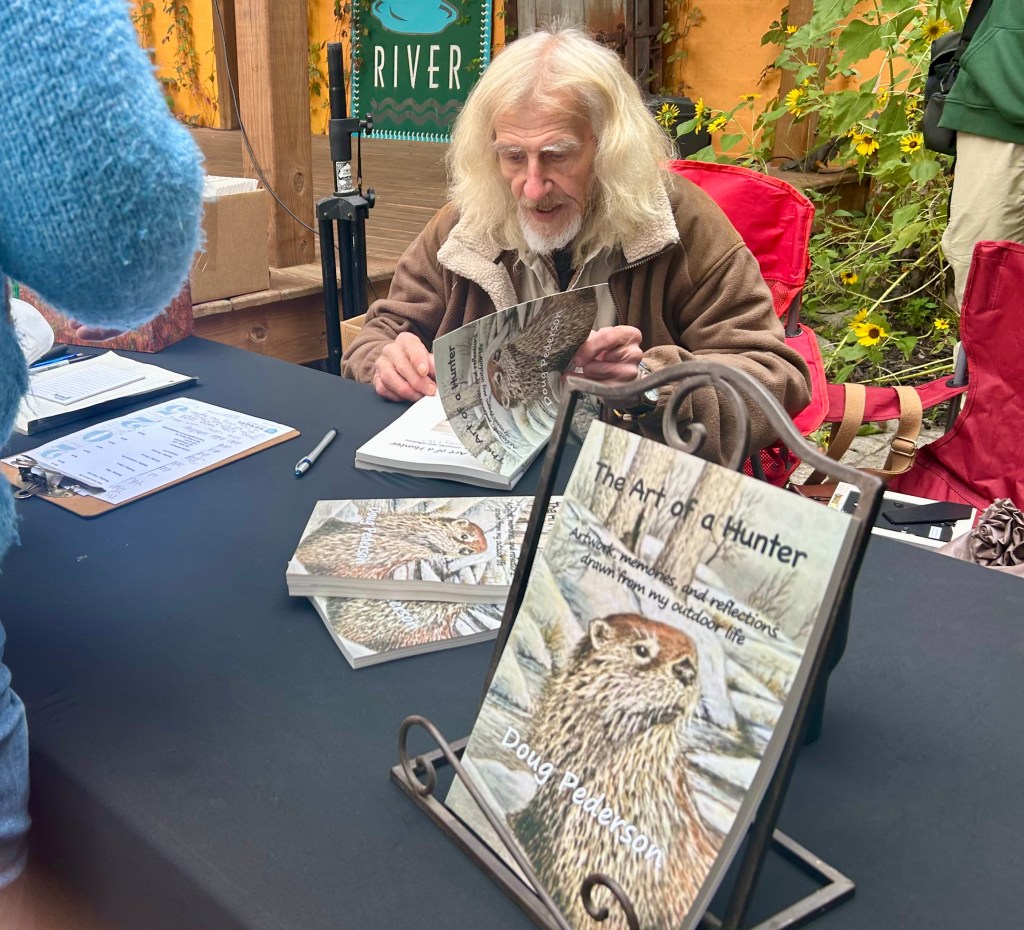

Pederson, who spent his Saturday morning signing copies of his newly published book of wildlife art and written thoughts in the courtyard of Java River, sold me a couple of “orphan” boards, and made at least another one into an incredible painting.

The back story: Several years ago an “ill-advised” couple talked me into building them a dining room table, so I called Don Schuck, a sawmill guy and wood artist up by Paynesville, to ask what he might have available. “Depends on what you want,” he said before suggesting he had some very nice maple that might work.

With a free day my friend and I drove up and she thoroughly loved the grain and feel of the maple so that was a go. Don, though, had another board set aside knowing I was coming. He’s just that way. Besides having an incredible grain and color, it was also a wood that showed signs of chaffing. “Five bucks, and there isn’t another one like it you’ll find anywhere,” he said with the wiry, and perhaps, knowing smile.

While starting to turn the maple this way and that … a key board with a dark wave resembling a flying crane would become the centerpiece … my orphan board was set aside. While intriguing, it seemed a bit short for doing much with it. One day coming in from the studio I passed this incredible board art painted by Pederson a few years before, a painting of bison where he blended the grain of the wood for the basis of a prairie mound. This is a fine example of his wood art and realistic wildlife paintings. This was a purchase either prior to or during an earlier Upper Minnesota River Arts Meander, an event he participated in from the beginning.

After passing the bison painting the orphan was quickly placed in the pickup and we were off to Pederson’s studio where I waltzed in and handed the six-foot plank over to him. “I don’t care what you paint, Doug. And there is no deadline. Stick it someplace and see what comes to mind.”

And, I forgot about it. Literally.

Months later, perhaps years later, he called. Said he had finished a painting. That if I didn’t like it he’d come up with something different. After arriving at his studio he presented me with the orphan framed with an incredible scene of common and hooded mergansers frolicking in a rocky rapids, using the grain as waves, all framed by a branched and weathered river sprout fighting against the midstream current. A minnow is in the beak of one of the mergansers. Besides being so realistic and amazingly artistic, it was a Doug Pederson through and through. How could you not be impressed with his artistry, his magic with a brush and his keen respect of the wood grain there as a natural feature within the art?

Oh, there was also the time upon leaving his studio on a chance visit that he had chunks of scrap slabs in a battered cardboard box by the outside door. I picked one that possessed a lot of character, a thick piece of weathered walnut. Paid him a couple of bucks before handing it back with the same request. “Here, Doug. Paint me something.” A couple of months later he called. On the darkened slab of walnut he had painted pair of otters peaking around a debit in the wood he used as a stream-side stump. He had sliced the slab in two, using part for a base to anchor the half with the painting. A cool shimmering of bark with a perfectly placed knot surrounding the base pulled the whole piece together. Pure magic! Amazing artistry!

All of this along with a couple of spalted maple vases with wildlife portrayals came to mind as I pulled into the only parking space available within two and a half blocks on either side of the street for his signing of his newly published book, “The Art of a Hunter.” This was a book signing I couldn’t miss, not after all these years of visiting Doug in his studio, of hanging his paintings, and not after learning earlier this spring when his son, Brook, after he called for me to pick up some walnut lumber he had milled, told me that his father had some serious health issues. Too many years of unmasked breathing of fine wood dust and a horrible smoking habit.

Despite a very chilly early September morning, the courtyard outside of Java River was standing room only. All the courtyard tables were filled with folks crowding along the side. Out on the sidewalk beyond the wrought iron fence they stood about two deep. Doug’s wife, Marie, who manned the shelves of the local library for years, and his sister, Marcia Neely, took turns reading excerpts as Doug patiently signed book after book as the line of patient friends and fans of his art continued to wade up to his table. He knew us all.

His book is a fine collection of his years of painting the prairie nature he so loves, and his many thoughts of man’s dealing with the creatures of nature, those hunted and those he lovingly observed over a lifetime as a prairie naturalist and artist. Just inside the cover are these words: “I have a hard time using the word nature as if it’s separate from humans. We are one and the same but we humans seem a little lost.”

Marie and Marcia talked about the processes this semi-reclusive artist and woodsman went through, collecting and creating the paintings included in the book before his sister told of how her now elderly and struggling brother suddenly became quite energized once he began writing the text. Perhaps it was a life enhancing experience. With help of a grant from the Southwest Minnesota Arts Council (SMAC), he and his family began curating the art and putting the text together in what became a 116 page collection.

“Some of my best experiences happened while sitting in the woods or on the water with a camera,” he wrote. “I called it ‘catch and release’ hunting.” Something I have been doing for years, and like my long time friend, my outdoorsy-ness is more observing nowadays with my camera rather than actually paddling and fly fishing.

Times move along and there is no longer a “Doug Cave” on the hill just outside of Montevideo. Brook remodeled his and his father’s old wood shop studio a year or so ago to convert it into an Airbnb. For years Brook continued to work the family’s tree trimming business where much of the wood he and his father used for their respective art was cultivated. As times moved along, Brook no longer maintains the old family business. And his father? He just published a book on his life as a naturalist and artist, a fine reflection of his legacy of wood and art.

If interested, copies are $25 apiece and can be purchased at either Java River or by contacting Doug at scrimdp50@gmail.com/.