There was a lull in the middle of the afternoon, moments between a Hands Off Rally and an Easter dinner with my son, on this the Saturday before Earth Day. Easter is a big thing for Jake; Earth Day for me.

First, his story: Years ago when living in a different group home he connected deeply with his primary caregiver who even on her Sunday’s off would come to take him to church. This beautiful Hispanic woman became a cross between a second mother, buddy and caregiver. It wasn’t long after his mother and my wife had died. She also made sure he was registered to attend a summer Christian camp within an hour’s drive of the group home.

Unfortunately, as happens with group homes, she eventually decided to move on. Yet her influence was so deep that years later church holidays and the camp continue to be his heartfelt necessities. He tolerates his father, who is more spiritual than religious. Where he finds peace within the folds of a saintly robe, mine come with nature.

So on this Saturday afternoon with a window of time before our dinner, my thoughts, as spiritual as they were, was to head to nearby Sibley State Park where I might amble through the dense, hilly woodlands in search of some early spring blooms of Hepatica and other woodland fauna. With the ongoing political turmoil we’re facing my traipsing through the prairies and woodlands have suffered greatly of late along with my spirituality. Sometimes I return home with few if any images, and most with little artistic effort. And still with a cluttered mind.

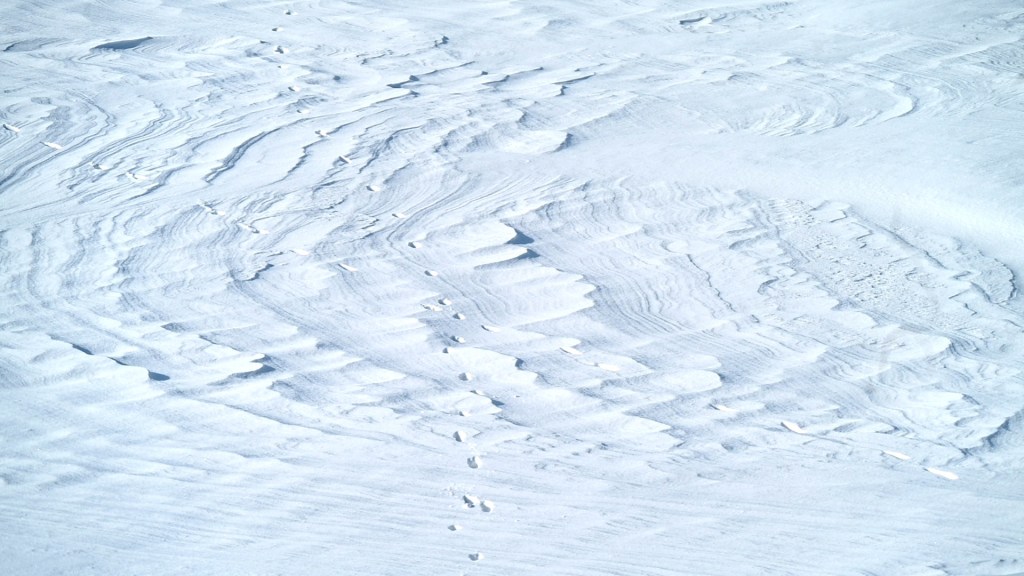

Before realizing it I had lost track of my bearings and was quite a ways north of the Sibley turnoff. Pulling off to the shoulder of US 9 to gather my thoughts, and to gauge a possible time frame, my decision was to head to the Lake Johanna Esker some 20 minutes deeper into the hills and woodlands of the moraine where a fine prairie “wilderness” awaited, if you can describe a grassland as such. This Nature Conservancy is home to perhaps the most prolific Prairie Smoke patches I’ve ever witnessed. Prairie Smoke and Pussytoes, one a brilliant pink, the other offering a gleaming contrast of white.

Although mid-April meant I’d likely miss both, it was worth a look. After arriving I sat for several moments to gaze at the distant esker, a tall narrow glacial stream bed towering over the adjacent prairie and now buried beneath layers of till, dormant grasses and gangly oak trees. That old stream bed is quite visible, unlike in the geological age when it lay buried beneath an ice sheet perhaps a mile straight up from where I was parked.

Eventually I grabbed my camera with a multipurpose zoom lens and ambled through the gate to follow a motorized trail angling toward the top of the nearest rise where typically hundreds Prairie Smoke plants would be blooming. Small leaves barely the size of a fingernail hugged the ground. Then, off to my left and down the rise a bit, my eye caught a hint of pink, and there it was, small and bowing gently toward the earth, a small Prairie Smoke blossom. Instantly I was onto my stomach focusing the lens. Nature now ruled. All of that confusion and nightmarish thought was suddenly gone.

After grabbing a few images, I rolled over to sit in the meadow, looking toward the esker, remembering a moment years ago while sitting here a pair of Sandhill Cranes flew over looking thoroughly prehistoric. Now in a distant wetland, a swan floated on the stilled surface, and high above a small pod of pelicans soared across a single cloud. Nature revived. With each breath my mind eased, little by little. Scents of the meadow and whiffs of spring meshed with the smell of earth. My eyes resettled on the poetry of the lone Prairie Smoke blossom, folded neatly into a perfect poem.

Moments after I stood and regained my balance, it was off through a shallow valley to the distant hill where perhaps I might find some Pasque Flowers, one of our first of the floral seasons. Finding none, I then ambled toward the massive mound of the esker where dormant prairie grasses and oak trees failed to hide the geological relic.

In time, and after a quick turn through Sibley amd dinner with Jake, I made a stop on the way home on a hill overlooking the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge where I’ve often visited for Pasques, and once again was rewarded. Now fully mature from when I was here just a week before, the blossoms begged for portraits, and I accommodated, once again lying on the ground on the hillside, working the aperture and shutter speeds, playing with the light, doing what one needs to do when making images of nature. Where before the blossoms seem to shrink from sight, they were now open and bold, lifting blueish petals toward the blue sky and drifting clouds.

It was a good day, recharging the soul while celebrating earth … just days before the official Earth Day celebration.

It’s a day offering many memories, from that first one at an auditorium in Denver while working for the Post, sitting with a friend as speakers stood before a nearly empty cavernous room and wondering if the celebration would actually catch on. That people would understand and pay attention to our lonely planet. A couple of years later I met and interviewed Earth Day founder Sen. Gaylord Nelson at a convention in Laramie, WY. Many years and Earth Day celebrations have since past, including when my Art of Erosion exhibit would be part of a Smithsonian water presentation at Prairie Woods Environmental Learning Center just a few miles from Sibley,.

And on this Saturday came the enjoyment of some special moments defying the man and his political henchmen who seems intent on destroying it all. Inspite of that chaos this was what I had been missing, that comforting peace that encourages my spirituality: peace sparked by a lone Prairie Smoke blossom, so colorful, so delicate, bowing poetically as if it in itself was offering a blessing to earth, caressing the prairie with such blissful grace. That was an offered poem I shall never forget.