Local historian, Judy Beckman, remembers when what our locals call the Lake Road was a bit more interesting than before it became “Buckthorn Lane”; back in the days when mums and apples drew folks to the area perhaps as much as the perch and walleyes in Big Stone Lake.

“Apple trees were ubiquitous,” she recalled “Part of the reason for that is that one of the main ways folks could get land was through the Tree Act, for which you had to plant so many trees and have them live for a certain amount of time. If one had to plant trees, you may as well plant something from which you could get fruit. At one time, based on electrical usage, Dragt’s Fruit Farm (now the campgrounds) was declared the largest apple orchard between Chicago and Seattle. Also at Eternal Springs there were about three acres of mums! Cars lined the highway on fall weekends for u-pick mums at $5 an armful.”

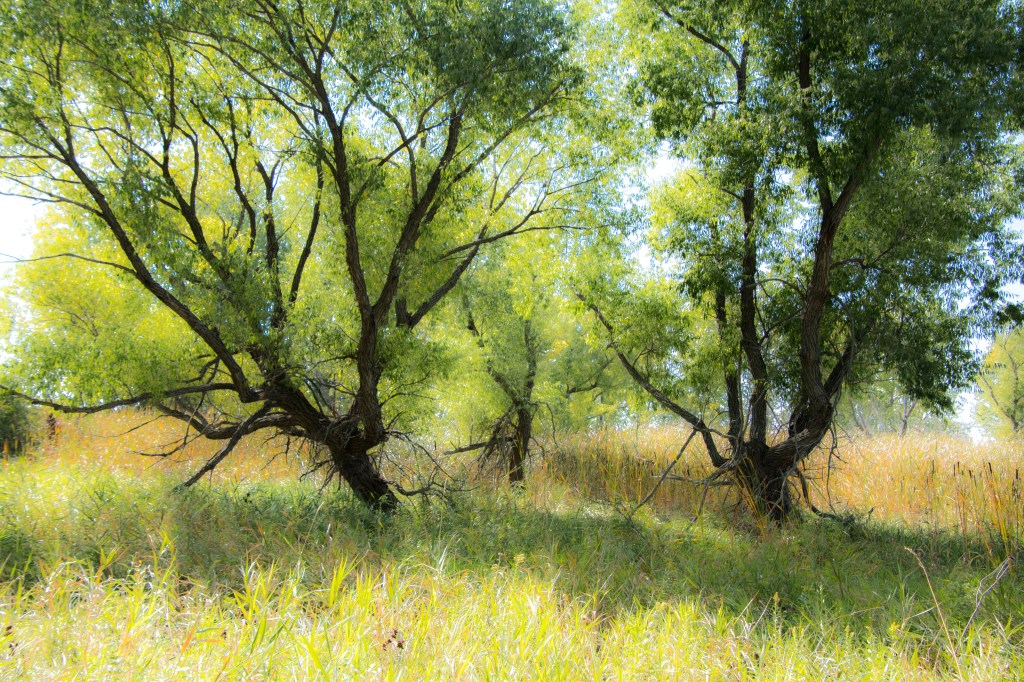

Although the mums are long gone, if my count is correct, only two apple orchards remain, both further up the highway. “In those days the hills were grazed, and you would see sumac … which you could see through. Not anymore,” she said. Driving what is officially ST HWY 7, long since paved over the historic ruts of a wagon wheel trail, the weedy buckthorn has literally taken over. Densely packed along with non-native as well as native tree species for the length of the highway to the Bonanza portion of Big Stone Lake State Park.

Perhaps now times and views are “achanging” … bit by bit. This began a few years ago with the “freeing the fen” effort along a mile and a quarter of the state highway fronting the lower prairie section of Big Stone Lake State Park. Now the city of Ortonville has joined in the cleanup effort by clearing off buckthorn brush and invasive tree species on the hillside of Nielson Park thanks to a Department of Natural Resources grant. Nielson was the home of a beautiful hillside-clinging stairway that weaved up the steep hillside along with other stone-work amenities found in the park, all gratis of the old Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the 1930s. This beautiful, timeless resource was hidden completely from view. No more.

Let’s begin up the road apiece with the freeing of the prairie fen, an effort that began about six years ago with the removal of hundreds of weed trees and acres of buckthorn from this 500-acre portion of the state park prairie. A view is now open down to shores of Big Stone Lake. Park manager Terri Dennison said the fen was discovered a bit ahead of the clearing work and that workers were conscious of caring for the delicate, alkaline-rich, peat-forming wetland, fed by a groundwater spring. It takes thousands of years for a delicate fen to develop, much like its rainwater-fed cousin, the bog. Escalating climate change, man-made tampering and water quality issues seemingly threatens both.

Initially it was surprising when the conservation workers (Conservation Corps Minnesota & Iowa) suddenly appeared and began the process of freeing that section of the state park from the fortress of trees and buckthorn that basically hid the lower section of the park prairie from view. Huge piles of tree trunks and debris were piled and allowed to thoroughly dry before being burned this fall. Tree removal work is still a work in process, Dennison said, although progress has reached a point where the prairie will be burned this spring. Fire protection swaths have already been cut along the edges.

“We realized that CCMI was not able to keep up with the buckthorn removal along with the trees,” said Dennison. “So we started doing contractor contracts to remove both the trees and the buckthorn. I think we’ll probably have some more cutting work along Meadowbrook Creek, or at least have CCMI take out the rest of the buckthorn.”

On a recent hike through the area with assistant park manager, John Palmer, the fen was pointed out, for it remains largely hidden by dense prairie grasses and other forbs. No, the fen isn’t readily visible with standing water as a bog might be, yet he hopes the planned burn will more fully free the fen. “We might see the small white ladyslippers return along with other plants unique to a fen,” he said.

It was equally as shocking when on a drive into Ortonville about a month ago to find the Lake Road partially blocked as workers downed and removed the choking buckthorn, huge pines and other non-native trees hugging the steep hillside that revealed the old CCC stonework, including a beautiful rock bridge I had no idea even existed. Then they moved to clear the portion facing downtown. Left to be cleared is a space between the two cleared areas. The nakedness of the hillside is stark.

A friend whose house is adjacent to the hill closest to downtown section admitted being completely shocked of the seemingly thorough denuding of the hillside, for she loved the trees for both their beauty and privacy. “What’s going to happen now?” she asked. She’s not the only one asking.

According to the local Ortonville Independent, the entire area will be reseeded in late February and early March with some 80 different prairie grasses and forbs.

“It will take a few years,” admitted Ortonville Mayor Gene Hausauer, adding that in the end the city-owned park will look like it did when he was growing up some 70 years ago. “It takes awhile for the roots to set in with the prairie grasses but it’s going to be beautiful.”

Hausauer admitted that some townspeople were shocked and complained about how the work initially looked. “I tell them to look across the lake from the hillside park to where the old ski area was in Big Stone City, for that’s how it will look in a few years. A green hillside in the summer, brown prairie grasses come fall and winter. Plus you’ll have the beauty with wild prairie flowers. I think people will really like it when they see the final results.

“That stonework is just beautiful,” he added, “and there are people around town who didn’t even know it existed until the buckthorn and crowded weed trees were removed. The stonework was done in the 1930s before I was born. We may hopefully get another grant to repair some of the damaged stonework that has been exposed thanks to the project.”

Perhaps in time Hausauer and others will then climb the stone stairwell meandering up the hillside to enjoy prairie smoke, coneflowers and a host of other native prairie forbs in full bloom overlooking downtown and nearby lake. Just as others may venture through the state park prairie further up the Lake Road to see and enjoy small white ladyslippers and other forbs common to a natural fen.

Both projects have attacked the fortress of invasive buckthorn and other non-native species that had gained a troublesome foothold for many a mile. Though both projects extend for less than a couple of miles, I’ll readily admit that it will be nice seeing something along the roadsides besides the impenetrable buckthorn; views that a few prairie flowers and big bluestem will certainly cure.