Category Archives: Uncategorized

Two Old Guys

“Our doctors would be having nightmares if they could see us now. Two old guys with questionable balance climbing over these precarious rocks!” came the soothing words of encouragement from dear friend and musical artist Lee Kanten in the midst one of our occasional saunters. Our climbing and balancing acts were on the ruggedly beautiful virgin outcrop terrain rising from the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge. True, neither of us are wholly well-balanced, and Lee has more bionic joints than I can remember. Me? I’m just old.

But, who cares? Those unnamed physicians were busy elsewhere, and arguments could be made about the just rewards of job security.

When we made our plans for our most recent saunter the sun was shining and blue skies with dotting clouds covered most of the earthen canopy. By the time we reached the Refuge a strong wind from the west had blown in an umbrella of grayness stretching to the edges of our horizons. We were not to be denied, especially after being told by a previous hiker that an unexpected waterfall was to be witnessed at the end of the paved trail off the central parking lot. So, off we went, each of us with a hint of a limp which we kindly pointed out to one another.

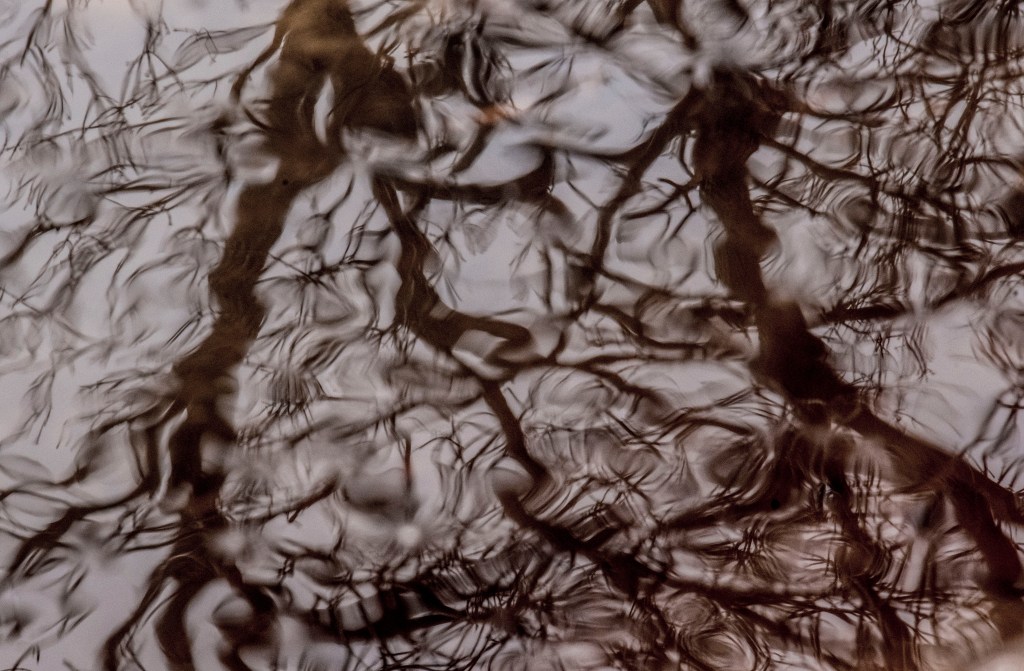

We had debated on whether to hike the Refuge or the lake trail at Bonanza, and opted for the hike on the trail through the outcrops, bedrock exposed by the ancient Lake Agassiz flood. At the apex of one of the more distant outcrops is a broad horseshoe-shaped bend of the Minnesota River that courses through the Refuge. That was my goal, at least, although I anticipated a reflection of blue skies glistening off a mirrored surface paired with colorful budding of riverine tree life. Perhaps another day.

Finding the waterfall wasn’t much of a challenge, for the paved walk took us directly to the bench next to the river (a perfectly rather secluded spot for self reflection). The falls was visible through thick woods off in the distance, and Lee surmised that it might be melt water being pumped from the gravel mine nestled next to the Refuge.

We weren’t long at the end of the paved path, and decided to climb up the craggy face of the adjacent outcrop to the walking trail we knew existed once we scaled the face. Up above the wind had a more wintry bite. The trail is one of our favorite for it winds through the picturesque outcrops and an oak savanna, and at various points offers great vistas of the Refuge prairie off to the southeast along with that vast flooded waterway that attracts migrating geese, ducks, wading birds, white pelicans, coots and other birds en route to their eventual summer environs. On our adventure the waters were basically barren of migrating birds save for a few coots coursing through the flooded grasses.

Eventually we meandered through to the top of the next outcrop where Lee suddenly stopped to verbally wonder about the power of the Glacial River Warren, the name of the breakthrough river of Lake Agassiz some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Geologists surmise that when the ice dam fractured waters sped through the glacial till like a cleaving sword at speeds of more than a million cubic feet per second. Till was tossed aside and scoured away down to the caprice, leaving behind a washed out valley of bedrock that varies in width at points of more than three miles wide, and is a gneiss and granite wonderland from the headwaters of the Minnesota River, that now courses through that trough of the old glacial river some 213 plus river miles from here to Mankato.

That scouring began just a few miles upriver from where we two old guys were climbing, and all these outcrops were laid bare by the flood. What’s fun is finding little holes in the gneiss where pebbles were spun by the raging waters leaving behind pockmarks in the stone you can easily still see thousands of years later. I’ve seen similar pitholes in outcrops as far southeast as Morton. These continuing outcrops give the Minnesota River Valley a special natural landscape not unlike the Boundary Waters … were it not for the polluting of the river waters themselves.

To crawl, walk and climb through such events of our natural history is daunting. Lake Agassiz covered what is now most of central Canada including all of Saskatchewan, North Dakota and northern Minnesota and was in it’s day larger than any existing lake in the world including the Caspian Sea. Remnant waters include Lake Winnipeg, Lake of the Woods, Red Lake and Rainy Lake, among others, as well as the Great Lakes.

The breakthrough drainage with River Warren was so disrupting and of such magnitude that it significantly impacted climate, sea level and human civilization. The huge freshwater release into the Arctic Ocean near Hudson Bay was believed to have disrupted oceanic circulation and caused a temporary global cooling. Yet these outcrops, here in the Refuge, was where it all began, and we two old guys were traipsing through what Lee called “an eye blink in time.”

Before Euro immigration this valley was home to various Native tribes, and local historian, Don Felton, often known as Babou, points out areas within the refuge where campsites were set up by the wandering tribes in search of bison and other game. He can also point out bison rubs where a fine sheen glistens off the granite and gneiss in the sunlight some 150 years after the last bison were believed to have grazed prairie grasses in the valley. There is even evidence of Petroglyphs hidden within the outcrops, but Babou and others are reluctant to show them for fear of vandalism.

We didn’t see much bird life on our saunter. A few robins and a Downy Woodpecker. It was a bit early for the warblers and Cedar Waxwings, which love to tantalize a man with a lens on such saunters later in the year. A small brownish bird flirted with the photographer by hiding in the dormant grasses and blitzing behind oak branches along the trail. I did capture an image yet have no clue of its identification.

When we finally reached the more distant outcrop where the horseshoe bend of the Minnesota River beckoned, the wind was fraught with a pelting of occasional raindrops. Some felt like sleet against the cheek, and we hurriedly began making our way back through the rocky maze toward the car. Although it might require a vivid imagination to suggest we two old guys made a sprint for our safety and comfort, we did make it back mere seconds before the rain actually hit.

Meandering through this landscape left naked by glacial waters rushing at speeds we can barely imagine is humbling, offering much in similarity to viewing of the Milky Way on a moonless night when you can grasp the insignificance of both human life collectively on what appears to be a most unique planet in a limitless universe, along with your own life within it. That “insignificance” pales, though, when you can also vividly view and hear the destruction of what remains of this unique planet in ways far more morbid and everlasting than that caused by the Glacial River Warren. We two old guys will long be gone by the time earth will become uninhabitable if current trends continue, as earth becomes a wasteland planet that global greed has forever failed to yield.

Sweet Music of Spring

Ah, yes, the sounds of spring! The music! I can now hear it as my annual “yard river” broke through to begin flowing this week, and my, what a lovely sound. More of a narrow ripple than a growling rapids, though sweet nonetheless. All of us live in a watershed, thanks to gravity, and gravity is the conductor! Listening Stones Farm is no exception.

Water droplets from the melt begin the journey in clumped drifts in the bluestem on the hilltop of the upper prairie, tunneling beneath the prairie grasses to join singular droplets off icicles hanging from branch tendrils in the grove and the melt from the feet of the cottonwood, dogwood and maples. Some course downhill from the crest of my neighbor’s crop field, all of it joining just above the wood shop to course toward the first of two small retention ponds we’ve had dug here.

Enough of the melt, which came rapidly thanks to the suddenly warm temperatures, offers a bit of what naturalist John Muir called “snow that melts into music.” Yes, the small stream courses through the yard as all this melt rushes through to the foot of the grove and an eventual escape into the county road ditch and with luck, perhaps even to the Gulf of Mexico. We just happen to be on this side of the Continental Divide that cuts across the “roof” of nearby Browns Valley, itself the “roof” of Big Stone Lake.

Hearing the soft lullaby here in the lawn made me wish for more. Not too distant is the Bonanza Education Center, the northern “half” of Big Stone Lake State Park and located a bit south of Browns Valley and the Divide. Bonanza is composed of a high bank cut through the prairie by the Glacial River Warren when the ice dam at the foot of the massive Lake Agassiz broke free near the end of the last glacial period. Much like the rest of the cut through the prairie, from here southeast to Mankato, the Minnesota River system, of which Big Stone Lake is the first of a chain of “river” lakes, are full of these ravines. Some include actual waterfalls.

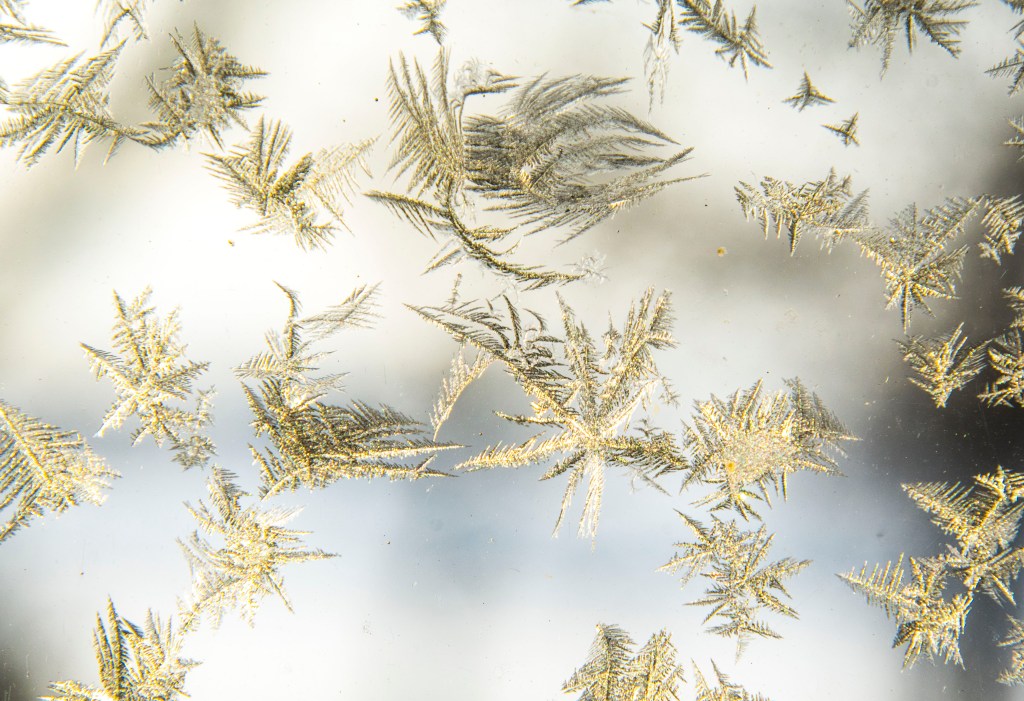

In Bonanza there are at least three rivulets coursing through these wooded ravines fed by springs that keep water moving throughout most of the year, even in winter. Now, with the melt, waters are raging through these ravines, and the music becomes more “concerto” than sleepy lullaby. A full symphony may occur further downstream in the actual river … provided there is enough for bank-high flooding. This week the concerto was lively as the melt waters spread out onto the frozen ice sheet to create a beautiful mosaic of melt and left over ice and snow. Solitary and stubborn ice fishermen still dotted the lakescape even as the sun lowered into a recent sunset.

Our melt has come quickly, or as weather columnist Paul Douglas noted in his midweek column in the Star Tribune, “We might be skipping straight to April weather.” This time last week temperatures hovered near freezing, and my yard and driveway were covered with a thick layer of hard, matured ice. Hard and gray, speckled somewhat at the fringes. I spent quite some time trying to break through an ice layer on the sidewalk between the house and studio, finally breaking through the last six-inch deep by four-foot long stronghold Monday afternoon. Ice on the driveway finally began to yield to the Bobcat delivering hay bales for the horses a day later. Then came the warmth, and Muir’s music.

What a lovely sound.

Here, though, it was rather ambient compared to that of Bonanza, and later on at the small creek just down the road that cuts along Meadowbrook to Big Stone Lake. All of it was lovely. All of it announced the end of winter. All of it opened arms to the warmth of spring and a change of seasons. All of it offers muse to the poets, and as Henry Williamson, the British author of Tarka the Otter, wrote years ago, “Music comes from an icicle as it melts, to live again as spring water.”

Indeed, this music is accompanied in the skies as Redwing Blackbirds, Snow and Blue Geese and their nearby cousins, Canada Geese, return to their northern breeding grounds. With the pleasing music of moving water, the sounds of the migrating birds offer us the woodwinds and brass to complete this orchestration of spring. Such blessings are so welcomed, so appreciated.

What a lovely sound!

Water in our small watershed is indeed alive and moving, dripping away from icicles and snow to course through our prairie island en route toward the Minnesota River and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. Daunting, isn’t it? In this freeing of the grip of winter, I doubt if I’m alone in feeling just as free as the melt itself. How heavenly such freedom feels. And, how lovely and satisfying is that orchestration of spring!

A Freedom of Expression

Hello! My name isn’t Wayne Perala. Hailing from Fergus Falls, Wayne is one of the best bird photographers I’ve known. He has perhaps filled his Audubon list with precise, accurate closeup portraits of many of the birds of our region whether in flight, perch or wetland, and superbly so.

Perhaps some of my images are similar to Wayne’s, although my quest is a bit different for my goal is to somehow use birds as an element of an image more so than a portrayal. Sometime I wish I had Wayne’s persistence and patience, his gift of leading on the wing. I don’t.

This was all part of my trepidation, or perhaps even procrastination … if not a little of each … this past week as I faced a deadline of an Audubon photography contest. Contests, although chock full of subjectivity, are fun, yet at this point of my life there is a loss of importance. Back when building my career there were many awards and honors accumulated through newspaper “clip contests,” state and national newspaper photography “contests” along with some fine newspaper and magazine writing awards. Yet, my two “Oscars in Agriculture” for journalistic ag writing now serve as bookends, though on my walls hang a couple of honors fully cherished including a beautiful Tokheim plate awarded to a “Riverkeeper of the Year.” The others? In boxes and drawers, somewhere lost over time.

My procrastination last week stemmed more from wondering if what I really liked about a particular images would be accepted more universally. My images are from what I see in the moment, hopefully with good composition, lighting, depth of field and so on, and if that happens to translate into something more, then, as was stated back in the day, “Far out!”

One particular image comes to mind. Just before an evening “blue hour” arrived I was “illegally” parked on a highway bridge over the Minnesota River as it meanders through the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge. Floating in the river was a gnarly log reflected in the calm, cream-colored waters. As I was focusing on the log a swallow suddenly dipped to the river surface for perhaps a gulp of river. Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Frenchman considered as the “Godfather of photojournalism” might call such a capture a “decisive moment.”

Decisive moments are what we strive for as photojournalists, be they as simple as an image of the swallow’s gulp near the reflected log in the mirrored surface of a river, or Cartier-Bresson’s own “Children in Seville, Spain,” a portrayal of child’s play in a street through a crater of a bombed out wall during the Spanish Civil War. Of course, there is no comparison between the impact of the two images, and I’m certainly not vain enough to place myself in the company of Cartier-Bresson. Or, Wayne Perala, for that matter.

Last summer I printed my river image and included it among the collection of matted prints I place both here at my studio and at some of the art shows, and often I’ve seen people pull the image out for a closer look. Finally a young man brought it to me to buy, commenting on the peaceful feel along with the colors. When I pointed out the swallow, he seemed to gather more respect for the image. Was this image worthy of the Audubon contest? Many more of what I claim as my favored bird images fall within this genre.

Here’s another example: Just a few miles away, and in a different portion of the Refuge, I made an image of cormorants resting on “piers” of stumps protruding from the waters. I love the feel and composition, although I fear the seemingly overall dislike and even hatred of cormorants. Perhaps this is a prejudice common only to Minnesota anglers who perhaps mistakenly blame cormorants for declining walleye populations in lakes … while dismissing the global warming effects on waters that diminish the ciscos and other “bait” fish walleye feed on. Certainly loons are much too loved to blamed for such atrocious acts against their favored fish.

Over the years I’ve captured many interesting images of cormorants, a member of a family of birds I initially fell in love with one dawn morning in the Everglades while watching and photographing Anhengas seeming to appear as feathered angels as sunlight glistened through their outstretched, drying wings. And, yes, their cousins, the cormorants, do the same thing.

One of my favorite Canada Geese images was at the North Ottawa Impoundment as they seemed to be in rest before the fall migration. I assume this was a family unit, which is common in that time frame and moment. Another is an image of White Pelicans at rest on a spit of an island in Big Stone Lake, and of a Wood Duck hen ferrying her newly hatched brood through pond weeds in Salt Lake near Marietta. There’s the Orchard Oriel snatching cattail fluff for its nest, and a Great Blue Heron perched on a dead cottonwood in the setting sun. The paired Sandhill Cranes that appeared out of nowhere while I was focusing on early summer Prairie Smoke. Their wings and posture was, to me, a portrait prehistoric in nature. Oh, and a Bob-o-Link taking flight in prairie grasses … over the years so many “decisive moments” have occurred in my pursuit of bird imagery.

Perhaps this sense of photographic freedom dates back to how I ventured into journalism. While in college a Forestry professor called me back as I was leaving his classroom to tell me that if I continued to pursue nature and the environment as a scientist that I would likely be “the most frustrated scientist ever. Your brain just functions differently than those in this classroom, and that’s okay.” He praised my writing and suggested that I concentrate on that instead of the sciences. He even introduced me to his good friend who was then the director of the Ag Journalism Department at the University of Missouri.

It was as if Eagle talons had been extracted from my nape. Suddenly I felt a sense of freedom for the first time in all of my schooling. And, now some 50 some years later, after a long career in photojournalism and writing, that feeling of freedom still exists. Procrastinating the Audubon contest was a surely part of that freedom, for my work doesn’t need to fit any particular concept or ideal, and I have no need for another possible award. My work is as free as that of a heron or eagle, defined solely by whatever space that might surround a particular perch or space in the sky.

I don’t know if Wayne Perala entered the contest, although I hold hopes that he has for his photography of avian species and life is superb and worthy of such honors. If so, and even if his photography isn’t chosen, he’s one hell of a portrayer of avian life, and whose work I thoroughly respect and appreciate. We’re perhaps driven by a similar creed, though our art is portrayed somewhat differently. No one would expect us to be “identical” twins.

A Calm in the Madness

A Calm in the Madness

If one looks, and not necessarily all that deeply, he or she may find calm in the “madness” of March, which is perhaps our most awkward month. March arrives with an uneven reputation and temperament ranging from the tournament heavy “March Madness” to an earthy “Muddy March” through the Shakespearian promise of the “Ides of March” and so on. It carries both a scrounge of winter past and a prelude of a spring to come, an in between month.

We Minnesotans are notoriously ingrained with the reputation that all of our high school championship tournaments are paired with halting blizzards, with fans known to argue that their preferred sport, be it wrestling, dance line, hockey or basketball, will bring the deepest and wildest of the seasonal blizzards.

Here in the country we anticipate a month of extreme muddiness as the snow yields ever so slowly to rising temperatures. We have hope the snow melt won’t happen so rapidly that the frozen earth isn’t properly prepared even if we can’t wait for it to be gone. If the surface snow melts before the ground below, torrents of raging waters and ice floes will likely clog the prairie rivers as happened in the spring of 1997.

Prairie towns along the Minnesota and its tributaries were threatened throughout the watershed and some were introduced to FEMA and other federal programs. Later in the spring canoers would marvel at seeing flood refuge clinging high in the treetops along the river, and at one bend of the Minnesota River below Renville County’s Skalbakken County Park, floodwaters stacked logs high up into the tops of the riverine trees like a log cabin wall.

Lest we not forget the winds. Those “Ides” of the prairie, where there isn’t much to block what comes across the Dakotas, lift dirt particles airborne from the barren cropping fields. There is little resistance once the snow cover is gone for there are too few cover crops being planted.

Enough of the perils, for there is another side to March. A much calmer side. That reawakening. Sometimes this calm is as small as observing the feathers of Gold Finches gradually gather more color. Or noticing that the Juncos are no longer at the feeders, or that the small and colorful Snow Buntings no longer linger along the roadways. While one would hardly call the Sandhill Crane migration, among others, as “calming,” yet those noisy and frenzied moments along the North Platte in Central Nebraska brings a sense of calming, for yes, spring is finally on the way. And I find that calming.

Migrations signal the reawakening of our prairie, this release from the grip of winter, as much so as the first blooms of prairie flowers. Indeed, there are some hardy flowers that may break through even in March.

Surely I’m not the only one who will forge a path to a known hillside where pasque flowers peak from scraggly brown and grayish dormant grasses. If we’re fortunate we’ll see our first pasque flowers bloom before the full release of winter comes in April. A few years ago I ventured to “my hill” – seems we all have a prized and chosen hill – to find a spring bloom awakening across the hillside. Not long after the initial bloom appeared we were hit with another blizzard. Afterwards I returned to find the snow had blanketed the blossoms, yet the blueish purple pushed through, delicately and defiantly strong.

Earlier this week I caught my first sighting of those seemingly haphazard skeins of snow and blue geese just north of town. A year ago in March we were blessed with a large flock with hundreds of birds that adopted the wetland just over the rise from Listening Stones Farm. This was the second time over a six year period this has happened. Other years I’ve had to drive across the county, or even up to Traverse County, to capture photographs of the migration. I don’t know where they are resting now, although I know they’re here. Somewhere.

I long to head to the North Platte, and might still depending on an upcoming procedure to solve a health issue. I was close to giving up on the possibility, although a drive this week to Sioux Falls to meet with a specialist churned up the desire to simply keep going. It felt as if I were already half way there. If I have a “March Madness” it’s the Sandhill Crane migration, and reports of the migrations have come from Illinois, Colorado and Nebraska according to the International Crane Foundation. The largest migration route is through central Nebraska where a quarter million Sandhills are said to funnel through.

Twice I’ve rented an overnight blind along the Platte to be closer to the birds as they come to the river for overnight protection from possible predation. As the sun lowers to the horizon large flocks begin descending down to the shallow waters and sand bars. As impressive and beautiful as the flights and landings are, the prehistoric din of the collective callings mentally transports you through the ages to prehistoric times.

Even if I can’t slip away for a few days, March will bring many rewards for this grounded traveler. As I write the release of winter is occurring. Calmly and steadily, on earth and above in the treetops and clouds – a calm within the “madness” of this awkward month juggling between seasons.

Countryside Tragedy

Fortunately a blizzard has reached the prairie, and hopefully one with enough snow to cover the numerous fields left barren after the fall plow down. This offers a few days of soil protection until the next melt. It’s simply a matter of time before the continuation of a countryside tragedy continues, as more dirt is released into the skies.

Which brings up the question: Have you ever wondered how many yards are in two tenths of a mile? I’ve got the answer for you … 352, or basically three and a half football fields.

A quarter mile? 440, or four football fields and nearly a half of a fifth.

For those who haven’t protected their tilled fields with a cover crop, or even just left stalks or crop reside alone following harvest, try to imagine how far your soil particles (dirt?) might have blown. Some will perhaps drive past their fields and see a buildup in the ditch and think that’s the extent. Some farmers will take front end loaders to lift the dirt back into the field … if that dirt is conveniently close to their field. Much of that blown dirt is not.

Not to pick on any particular commodity farmer, last weekend while driving past a farm I noticed the just how distant his dirt has blown, although country terrain and trees helped in keeping the dirt reasonably close. So here goes, starting at the lip or edge of a conservation-tilled field to a quarter mile away:

Remember, this is mid-February, and crop cover won’t be high enough for soil protection until late May or early June, depending on the crop. And this isn’t an only example. Here are a couple of images taken in Lac qui Parle County late last week.

If the snow from the blizzard per chance covers the fields there will be a temporary respite. Otherwise a majority of the fields throughout SW Minnesota are simply barren and won’t be planted until late April, May or June … leaving fields and their valuable soils vulnerable to the prairie winds.

Is there a need for cover crops? For protecting valuable soils being farmed for commodity crops? I’m asking for a friend … perhaps one who has yet to be born and who in his or her lifetime might desire something to eat.

Linking us to the Heavens

A full moon has risen here over the prairie reflecting flecks of snow swirling in a brittle breeze. Depths of our long winter. Now in the middle of February with spring feeling so ever distant, word comes that one of the highest number of Sandhill Cranes have already arrived along the North Platte in central Nebraska. This high number of Sandhills are more typical in the first or second week of March, according to an ornithologist with the Crane Trust.

Maybe time is now measured for this present grip of winter. Bless the cranes!

If swans form creative art on still waters, cranes link us to the heavens. Such promise gives me hope while bringing back a wonderful memory from this past summer when a dear old friend, Michael Muir, and I followed a visit to the Aldo Leopold digs near Baraboo, WI, by pulling into nearby parking lot of the International Crane Foundation (ICF).

Known for his reputation around Dubuque for his sarcasm, which may have been chiseled and honed back in the late 1960s when he was hanging with a small group of us fledgling journalists at the Telegraph-Herald, he blurted, “Realize, of course, that this is a ‘crane zoo.” At that precise moment my eyes were focused on a crane sculpture so I didn’t catch the twinkle in his eyes that typically accompanies such a comment.

Michael wasn’t too far off, all sarcasm aside. This wouldn’t hold the same magic found in the midst of a migration, nor was this the intention. Enclosed in spacious pens are all 15 worldwide species of cranes, each pen perhaps an acre or more in size with each containing a wading pond. His “zoo” comment referenced overhead netting stretched over each pen to keep the birds enclosed for the wealth of research being conducted on the various species, some of which are bordering on extinction. The ICF is, after all, a research facility that has operated here since 1973, and education is a huge part of that effort. Eggs are collected and moved to a separate facility that was off limits to visitors. Work here is ongoing and perhaps may lead to keeping some of the more vulnerable cranes from extinction.

Each species was paired, and none seemed too concerned about much of anything, squawking and meandering through their respective pens. Seating areas at each of the individual sites held both educational panels and maps of where one would find them in the wild. Each map indicated both their wintering sites and summer breeding regions along with their migration routes.

Of the 15 species, all but four are considered vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered. One would think our very own Whooping Crane heads the list of the critically endangered, yet it’s the Siberian Crane that claims this dubious honor. The Whooping Cranes aren’t far behind, however. Among those that aren’t on the list are the Sandhill Cranes, and there are even hunting seasons in some states for them. Or as Michael quipped, “What’s that about?” Without sarcasm.

In the words of the ICF, “Reverence alone, unfortunately, has not been enough to sustain the world’s crane populations in the wake of mankind’s rapacious lust for land and resources. Squeezed into ever-shrinking habitat reserves, nearly half of the fifteen species of cranes are presently threatened or endangered, qualifying the family Gruiidae as one of the most pressured groups of birds on earth. The ICF has pursued a multidimensional program of scientific research, captive propagation, education, and preservation of crane habitats worldwide. In these efforts they (the cranes) have made great strides.”

Although my first sighting of Sandhill Cranes was in the San Luis Valley of Colorado in the mid-1970s (where I also saw my first Whooping Crane), heading to central Nebraska and the Upper Platte River may become an annual pilgrimage for me. Yet, what caught my attention at the ICF was both in the number of worldwide species as well as the unique differences between them. While the ICF exists for education and research, for me their site offered an unexpected and captive experience for my photography.

In my pursuit I no doubt bored my dear friend, although he was patient and kind. I found myself mesmerized by the different plumage of the crane species, birds I will likely never see in their natural habitat. Especially those that migrate between the Far East and the wilds of Siberia along with those from the African Plain.

I found myself standing and focusing on each of the pairs, some longer than others. Our two native species bookended the loop, beginning with the Sandhill Crane next to the visitor’s center. At the very end were the Whooping Cranes, and their enclosure came without the overhead netting. In between were the 13 other species along with trails that also led off into a 65 acre prairie that housed the distant main research facility.

We were the first to enter the facility that morning. Those in the gift shop and the “rangers” who mingled with the guests were all knowledgeable and helpful, answering questions they’ve no doubt heard so many times. For example, this is one was answered at least a half dozen times that morning: “Perhaps the easiest way to tell cranes from herons and egrets is that cranes fly with a straight neck whereas herons and egrets do not. Their flight is with curved necks.”

Michael and I spent perhaps our longest time observing the Whooping Cranes, who were joined by a nervous number of flighty Cedar Waxwings. When we entered the vast seating area facing the Whooping Crane pen the pair was lounging in the shaded grass. Eventually one rose and meandered around the bank above a small pond, then threaded its way through the knee-high grass to the edge of the water to drink. We had entered this particular compound close to noon, so the heat and humidity had increased significantly since our arrival three hours earlier. Soon the second crane stood and ambled down to join the other one. It was felt as if we were infringing on their privacy. That feeling seems rather imminent around Whooping Cranes, birds earning a reverence akin to worship. Yes, worship, for some cultures, particularly in Asian countries, places cranes in such status.

Cranes are particularly prominent in the art and mythology that dates back to the earliest Asian civilizations. The Chinese consider a crane as the prince of all feathered creatures giving it a legendary status, embodying longevity and peace. Cranes are believed to be mythical creatures with lives lasting for thousands of years. The Japanese are particularly fond of cranes, and their paper-folding origami is a traditional art form. To them cranes are often referred to as “birds of happiness” … their wide-spread wings believed to provide protection. Mothers will recite this traditional prayer in concern for their children:

“O flock of heavenly cranes … cover my child with your wings.”

The day before Michael and I visited the ICF we had paid homage to the late naturalist Aldo Leopold, whose farm and cabin are nestled nearby along a bend of the Wisconsin River. Leopold was as enamored by cranes as were his Asian brothern far across the seas. Mentions of the Sandhills can be found throughout his writings, and he gives particular homage in his essay, “Marshland Elegy.”

“Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language. The quality of cranes lies, I think, in this higher gamut, as yet beyond the reach of words,” he wrote.

The ICF was a special place, and graced me with some special images. Now, as the snow swirls in the gleam of this full February moon, I think of the North Platte; of peering through opened windows of a chilly plywood blind listening to the thousands of Sandhills seeking protection in the shallow waters and sandbar isles up and down the river. Of watching their unique beauty in easing from the skies to the protective waters; and again, hearing them rise from the darkened river in hopes some will remain until the sun provides enough light to witness and photograph yet another magical moment … when the heavenly cranes may once again cover my soul with their widened wings.

And now, thanks to ICF’s “crane zoo,” to fully realize the magic and beauty of similar migrations extending across many lands and waters.

An Escape to an Ice Floe Ballet

Across the near water where the eagles soared singularly or perched in packs on ice floes, a blueness, a cyan yielding to violet, blanketed the river in either direction as evening grew ever closer. Yet, above the Mississippi River, the sky would have made sweet fruit happy with glows of amber and orange. Somewhere back over the Read’s Landing bluff the sun was nearing a distant horizon. At that moment, though, our ambient light at the foot of Lake Peppin was fit for gods.

Ignoring the dozens of eagles were numerous swans, especially in the distance near a wooded island across from Wabasha. Dozens, and certainly more than 100.

If the eagles were from the “hood,” the swans offered contrast by creating a sweet ballet, long necks often in symmetry, always poised with grace. Thoughts of Tchaikovsky? The contrast couldn’t be more bold between the raptors and floaters, though each were equally captivating.

These birds and colors were to be celebrated only briefly, for nightfall would come ever so swiftly. Our planet spin never slows though we’re often unaware and even immune in both deep darkness and blinding light. Sometime watch a shadow as it moves either side of mid-day, for shadows move with the same swiftness as a setting or rising sun. One mid-morning I was captivated while watching shadows move across the crevices and archways of the St. Paul Cathedral from a hotel window. Ever moving, constantly changing.

Other than Read’s Landing my month of January was unlike planet movement due to some health issues … which actually began after that near perfect afternoon while visiting fellow journalist friend, Anne Queenen. Her second floor apartment windows offered a perfect photography “blind” just a roadway and a set of railway tracks from the western bank of the Mississippi. Freighters and Amtrak’s Empire Builder between St. Paul and Chicago ply the tracks, and the roadway is a frontage road off Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 … again revisited.

After Christmas I had fought a cold/flu with sneezes that rattled the soul, although swabs of the nostrils indicated no Covid. Now, several tests later, I’m still negative, although the health issues have me cornered here on the prairie. Blessed with a catheter since my trip to Anne’s, my home here on the prairie is where I’ve been, my camera and my writing unattended. My isolation has felt rather extreme for an extrovert like me. I had thought the autumn and approaching winter was slow. One keeps learning.

All of this isolation has brought, strangely enough, a sudden and growing pressure … a sudden sense of seeking escape; to explode and explore. Ah, the three “e’s.” Escape. Explode. Explore.

Isolation from the flu/cold was what I was feeling a few weeks ago when someone posted a picture on social media of swans in flight from Read’s Landing. By then I was healthy and fit, and felt a strong urge and acted on it by sending Anne a message after a thought, a bit of recall. When we had last communicated in the autumn she was living somewhere south of Redwing along the Mississippi River. I couldn’t recall where exactly, so I sent her an email. She responded almost immediately. “I actually live in Read’s Landing,” she wrote back, “and yes, you are most welcome to stay here with Bode and me.”

Bode is a lovely though incredibly shy dog of blended breeds and kept a close eye on Anne’s guest as he moved from window to window looking for new images of the eagles and swans. Which the visitor did until nightfall.

After darkness settled in over the river, Fred Harding, Anne’s close friend, joined us for a wonderful dinner. All this beauty and fellowship were mere moments before my more serious health issues revealed themselves after a totally sleepless night. That would come later, though.

Thankfully Anne was happy to see me. Although we have corresponded infrequently over the past several years, it has been some time since we’ve seen one another in person. Over the years we have jointly though independently reported on many of the same issues: A rock quarry proposed on the original outcrops “released” by the Glacial River Warren at the headwaters of the Minnesota River; issues of soil erosion and water quality; and most recently, on cover crops. She was actually working on a cover crop story when I arrived.

While I walked from window to window focusing on the beautiful eagles and swans, she talked about possible places we could go for even better and closer views. On the other side of Lake City I had passed Fondulac State Park, and I promised myself I would stop on the way home. Another time, perhaps, and Anne has promised some beautiful trails. While being treated by nurses at the hospital in Wabasha, one had talked about pull out spots near Alma, WI, down the road from where she lived. The list kept growing … and Anne promised on my next visit we’ll take it all in. Whenever I’m ready to “explode” from my isolation. To escape and explore!

Now, nearly a month later my issues remain and I’m yet blessed with a catheter. I’ve been reading. And reading, and more reading. So many friends have reached out since learning of my condition, and have added much light to the darkness I’ve been feeling. Then, ever so slowly, the pressure pokes through along with those urges of the three “e’s.” Pressure or hope?

All fall I’ve looked longingly at my small camper trailer. I haven’t used it since my former fiancee and I returned from a trip to Washington state back in July. I simply couldn’t convince myself to hook it up and take off somewhere. Not even to a nearby state park. For two years now I’ve wanted to escape and explore Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in New Mexico. And there is always a winterish escape to New Orleans, or more specifically, the Cajun Triangle across the Atchafalaya Basin. I have so many wonderful memories through the years from the Triangle, and if there is a place in the South that feels close to home, this would be the place. Now my eye is meandering toward returning to central Nebraska and the Sandhill Crane migration. Or, to the Loess Bluff National Wildlife Refuge in Northwest Missouri. And, an invitation is open to revisit Read’s Landing to fulfill those promises of a special friend.

No, I’m not out my funk quite yet, although as we ease past what is hopefully the worst of winter my mind has begun to wander once again. Hope. There are taxes to do, and hopefully there will be some answers to my health situation. A large part of my hope is that this overbearing isolation is merely temporary and moves with the speed of our revolving planet, and that I will soon feel the welcoming bumps of the byways. That I can explode from this isolation. Escape, and then explore whatever awaits. Whatever may be.

Winds of Winter

Seven days into the new year and I stare at a long blank white page in my journal. My water colorist friends would likely call this a blank canvas. I sit at a small, oblong table in a room few have seemingly wanted or felt comfortable in although it once housed a well respected political blogger roommate and then the woman I was hoping to marry before she took foot. Here, though, she crafted dozens of masks to help others face the Covid pandemic and some warming and colorful quilts along with some beautiful water color paintings.

So there is a bit of semblance.

For now it is a “study.” Perhaps if I’m fortunate, I won’t have use of the room for long. For the time being, though, I’m claiming it as a place to think and write since winter has made my studio office so cold the space heaters can’t even keep my fingers from feeling numb.

This is a nice perch overlooking the south meadow of my prairie where the stately Big Bluestem and the poetic Sideoat Gamma, along with numerous other forbs and grasses, have knelt in huddled defeat to both the winterish prairie winds and the choke of snow. The smashed and bashed prairie grasses make a heavenly retreat for a rabbit I spied earlier this morning, though they lack offering good hiding for the pheasants. Unless the colorful birds have burrowed into the depths. The spindly stout stems of thistle and milkweed will eventually yield as well.

Barely visible through the whitened snow blown haze are the rainbow-ish outer arcs of an icy halo commonly called a Sun Dog, or parhelion. Seeing one typically reminds me of a photographer friend who had flown in from the Netherlands, who as we drove across the frozen prairie on a day not unlike this one, though minus the wind blown haze, became mesmerized by a Sun Dog. I pulled over and she climbed out of the warm car into the frigid air to take photographs. Indeed, she still has a print on her apartment refrigerator outside of Amsterdam. She wasn’t out long, and later claimed to have never been so cold.

I was thinking the same these past few days with temperatures in the negative teens in the “heat” of the day, before lumbering deeper into the minuses … the twenty and thirty below temperatures come nightfall. As I look through the window at the haze over the prairie and across the tilled fields more distant, though warm I still since a shiver. The horses in the small paddock on the other side of the house crowd together as they munch their hay.

Tonight my musical artist friends are gathering in town for a burger before heading over to Lee Kanten’s studio to sing and play. Moments ago I offered my regrets. My near mishap earlier in the week has made me extra cautious. I was on the way home from Willmar about 90 minutes east of here, where I had gone to drop off my son’s stuffed animal sleeping buddy and the Christmas gifts he had left behind. According to warnings from the National Weather Service, a blizzard warning had been issued and was expected to hit after dark. Snow along with high winds.

Although I had left early in the afternoon, I figured if I made it home before dark (around five-ish) my trip would be uneventful.There was ample time. Then a long tar sand train with too many cars to count caught me on the outskirts of Willmar. My car was basically trapped between two others as we sat there for a long and grueling 20 minutes. I was looking more at the gray sky than the train itself, which was moving as an old man walks before it stopped to block the crossing. Cars behind me began shifting, and eventually I was able to back up and turn around to head east toward another possible exit.

About 40 minutes later as I was going through the small prairie town of Appleton when another freighter coming through brought the arms down across the tracks before lumbering through, Another 15 minutes or so was lost as darkness settled in. The highway between Appleton and Ortonville, though clear, varied between decent visibility and clouded vision from the winds of a ground blizzard. By the time I reached the gravel road leading to Listening Stones Farm the visibility was next to zero, and I veered my car off the road into a ditch.

I was fortunate to reach my renters, the Thorsons, on my cell phone, and they soon arrived in their large pickup to pull me out before escorting me the rest of the way home … more than two miles away. Modern technology and a kind and compassionate family had made perhaps a life saving rescue. So, yes, I’m now being extremely cautious.

Much like the stately Bluestem, I now kneel cowardly to these winds of winter. Instead of braving the elements I’ll cuddle on the couch with Joe Pye with a book in front of a fire listening to the wind roar with a potentially deadly gusto. As the “blue hour” eases in I can barely see the line of trees across the road. Wind blown snow once again creates a haze now more bluish than white. Temperatures are once again forecast in the minus twenties.

And, I’ll be laying on the couch with a book with the fireplace ablaze. Safe and warm, just a wall away from the winds of winter.