One of the traditions I so thoroughly enjoyed in my long ago newspaper years came near the end of December when we were asked to sort through and submit our favorite image, or images, of the year just before New Year’s Day. This gave layout editors fodder for a traditionally slow news week between Christmas and January 1.

For us this was a chance to review the stories and our photographs. For me, that review was crucial to my growth as a photojournalist. Did the imagery seem to hold up to previous years, or was there a lag? Was there a sense of growth? Had my “eye” for composition, working with natural lighting, choosing an appropriate focal length worked with the news event or photographic moment?

My concern nowadays is if my “eye” has held true since my retirement as I’ve moved to more closely document our last one percent of the glacially-blessed native prairie and wetland ecosystem that has been systematically and throughly destroyed by mankind since the 1860s. This destruction and my care for recording the remnants photographically has been stated repeatedly in my artist’s statements that have accompanied my exhibits and art shows.

Since moving more into a creative arts community this tradition of reviewing my past year of imagery to choose 12 of my favorite images has continued over the past 11 years. My choice and intent is not to choose just one but a dozen, initially to pick one for each month. It didn’t take long to realize that better images were being left out, and since this is my choice on what to show, that concept died a quick death.

While the annual review is fun, the intent remains the same — seeking a measure of growth, of how my “eye” might have evolved over time. So, here we go, along with a few comments for each of the images are my dozen for 2025. If you wish for a closer look simply “click” on the picture to enlarge it. Meanwhile, thanks for your kind comments and support of my work through this and for all these years.

Just outside of Big Stone Lake State Park this piece of the glacial moraine that separates the River Warren river bed, now Big Stone Lake, and a huge, miles long ravine that is home to Meadowbrook Creek. This interesting afterglow was one of those “you had to be there” moments giving the native prairie the appearance of a staged play.

Moments before this was captured, I was pulling out of the fisherman’s lower parking lot below the Marsh Lake Dam when a pod of pelicans flew over. There was no chance for a picture, and I left the area disappointed. At the “T” at the end of the dam road, I took a left hopeful of getting closer to my road home and ended up at Curt Vacek’s machine shed. A dead end. As I headed back another pod flew over. Both times dozens of pelicans seemed to be heading toward their island refuge. Hopeful, I sped back to the dam, backed onto the dike and just as I rolled down my window and grabbed my camera, this pod flew over exhibiting grace and aerial choreography. Pelican flights often seem to offer such grace to our prairie skies. That the birds stood out against the subtle grayness of a cloudy sky makes the picture. One of my favorites from over the years.

Ever since moving here I’ve had an eye on this lone tree on the bank of a long drained prairie pothole lake that before being ditched and drained stretched for miles and over what is now many commodity grain fields. From the bottom of the old lake bed the tree looked to be in line with the sun of the Summer Solstice, and once again I was blessed by nature when a lone bird flew into the sunset.

Between my boyhood hometown of Macon, MO, and neighboring Atlanta, the Missouri Department of Conservation damed a channel of the Chariton River to create a multi-mile lake and eventual state park. After driving through the park we exited through the far north gate and turned toward the major highway when we crossed a high bridge at the last “finger” at the head of the lake. This wasn’t my initial view, yet the swallows flying from beneath the bridge and silhouetted against a distant brewing storm caught my eye back in mid-July, and again in review.

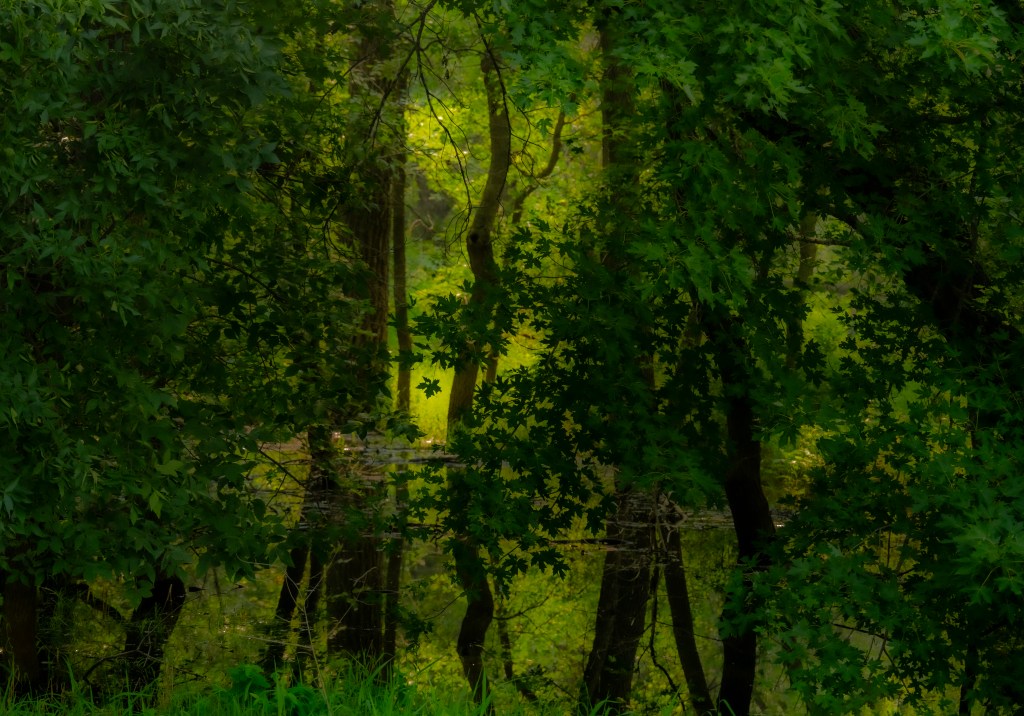

Although we had a cabin on Lake One on the lip of the BWCA, we did more exploring around the area because my favorite woman lacked comfort in a canoe, and in those adventures we stopped at Bear Head Lake State Park, which after years of being in and around Ely I had never noticed. We took a hike on a wooded trail that ended up at Norberg Lake. The calm waters of this small lake surrounded by age-old timber offered an incredibly soothing moment, especially in our distanced escape from the political chaos of the summer. This scene was a reflection of my calmness and comfort.

Just a few miles from home a lone pelican and the ambient afterglow reflected in a wetland. More of what I call poetic photography. Often I leave home just before sunset to drive around the area wetlands, and unlike most of the counties around us, it is estimated that 15 percent of the original wetlands still exist in Big Stone County compared to less than a percent elsewhere in Western Minnesota and Northwest Iowa. And it seems that every year I’ll come across a lone pelican in a prairie water wetland. This was my moment in 2025, a moment of peaceful bliss.

In my exhibit this image carries a simple title: “The Leaf.” Yes, this singular leaf caught my eye within the midst of the “forest” in the high Minnesota River backwaters of mid-summer at the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge. I love the angular tree and its reflection, yet the “individualism” of the stark leaf is what caught my eye. I guess I’ve always been sort of a “loner,” like “The Leaf,” feeling a bit out of step with the society that seems to surround me.

November, and the “super” moon at Crex Meadows just across the Wisconsin border with Minnesota. Sandhill Cranes are my favorite bird and this image is one I’ve visualized for several years. An unfulfilled dream, if you will. With the promise of a full moon along with prayers we would have a cloudless sky, we drove nearly five hours across the state to Crex and got a motel room. We then found a vista that might offer a gigantic full moon rising along the horizon, along with hope that the cranes returning from the nearby stalk fields would offer a blessing. This was among several images of cranes flying through that incredible moon, and this was my favorite of the bunch. Once again nature provided a special blessing!

Then, the following morning in the “nautical” twilight … again, Sandhill Cranes. Have I said I love them? Even after a half dozen trips to Central Nebraska each March, along with various outings to both Crex Meadows and the nearby Sherburne NWR between St. Cloud and the Twin Cities, I can’t seem to get enough “crane time.” My first viewing of Sandhills was on a organic farm near Monte Vista, CO, when my now late friend, Greg Gosar, whose farm I helped feature in a Money Magazine story, came running into the house to ask if I wanted to sneak up on a feeding flock of cranes in his wheat field. We sauntered as quietly as possible up a sandy draw before leaning against the bank to see the birds. A highlight was a lone Whooping Crane back when their number was in the low 70s, along with what Aldo Leopold called the “trumpets in the orchestra of evolution.” This was in the late 1970s, and I’ve “chased” those beautiful songs and flights ever since.

Northern Lights, the auroras of the heavens …. a Cinderella-like moment for the normally muddy Eli Lake in nearby Clinton. I love this view of this disregarded lake on the edge of town along US 75 and a county road. Certainly I’ve witnessed more spectacular Aurora displays, yet what attracts me to this image is both the natural composition along with the reflection highlighting the colors even as “subdued” as they appear. Despite the shallow waters, seldom seen as blue, the Aurora awakened the waters from its normally placid blandness — an Aurora that provides a glimpse of normally unrealized beauty.

While we’re on Northern Lights, this was captured with my cell phone when the settings on my camera got messed up. This was a spectacular display in all directions, and taken over a prairie wetland at the lip of our prairie looking toward the Northwest. While the October 10th display was considered the highlight of the year’s displays among us Aurora geeks, this display might have been an equal, offering both vivid colors and that hum from the heavens … something you don’t always hear, with colors you seldom see this far south.

Another moment from a nearby wetland, a Great White Egret lifting from a vista featuring a setting sun. Once again when I look through my couple thousand images of wetlands, I feel such a sense of loss. Besides the benefits of recharging the underground aquifers and cleansing agricultural chemicals from the runoff, they benefit wildlife and provide incredible beauty to the prairie for many of us. The 99 percent of destruction of the wetlands is such an incredible loss, and a loss that keeps me in constant search for poetic imagery. And in this instance, I was once again blessed by Mother Nature.