Long before he became a toddler, we took our son, Aaron, on a short hike through a small riverine woodland just south of Prescott, WI, on an October afternoon. He was in my arms, small yet eager, looking over my shoulder before uttering what my late wife, Sharon, and I claimed was his first ever word: “Preee” he said. It was, indeed, for the afternoon was chummy and sunny, the leaves colorful and the currents of the Mississippi River easing by slowly.

Now, entering his fourth decade, Aaron balances his writing and theatre training into stand-up comedy routines in both English and Norwegian in his adopted home of Bergen, Norway, while studying to become a nurse. In the process he holds fast to his love of nature on long hikes with his wife, Michelle, and their dog, Storm. When I offered him my newest word of his adopted language, he knew precisely what “friluftsliv” meant, a discipline he practices whenever possible.

Pronounced “free-loofts-liv”, this translates into one’s thorough enjoyment of nature. Friluftslive was popularized in the 1850s by the Norwegian playwright and poet, Henrik Ibsen, who used the term to describe the value of spending time in remote locations for spiritual and physical well being. If you’ve spent time in Norway, and especially in the breadth of Telemark County, which includes Ibsen’s home in Skien, the county extends from seaside villas into the heights of the mountains to provide ample opportunities to soak in as much friluftsliv as humanly possible.

I can now add “friluftslive” to the Japanese term, “shinrin-yoku,” which translates to forest bathing, into my limited vocabulary. Color me guilty of loving and practicing both disciplines. Forest bathing encompasses meditative disciplines while friluftsliv seems to simply embrace the enjoyment of being in and enjoying nature. Friluftsliv was a word that came from an American-Norwegian friend, Judy Beckman, during a recent house concert here at Listening Stones Farm featuring author-song writer-musician Douglas Wood and his accompanist, Steve Borgstrom. One of their songs, she said, brought the term to life, which I can thoroughly understand since Douglas’ music is ripe with references to nature and, well, friluftsliv.

Enjoying the beauty and peacefulness of nature comes naturally for us here in Big Stone County on the Western “coast” of Minnesota. While we lack stave churches, mountains and fjords of Norway, we do have the last gasp of the mostly extinct prairie pothole biome, meaning we retain some patches of prairie along with having several potholes or wetlands dotting a somewhat rolling landscape. Nature settings in a natural environment.

How natural? It was here that the massive glacial Lake Agassiz, a large pro-glacial lake that spread across the upper regions of the northern tier states into much of the Canadian prairielands during late Pleistocene Era, and was fed by melt water from the retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet at the end of the last glacial period. When the ice dam broke at modern day Browns Valley, it cut a huge river channel deep into the width of what became a natural prairie extending across SW Minnesota and NW Iowa. At its peak, Agassiz was larger than all of the modern Great Lakes combined, and one could suggest that Lake Winnipeg, which is longer than our current Minnesota River, is a remnant of Agassiz. If one uses his or her imagination, the remnants of that glacial activity surrounds us here both in real time and as “ghosts” of the Pleistocene.

That break at the top of what is now Big Stone Lake created the Glacial River Warren, which came rushing through at speeds scientists estimate at more than a million cubic feet per second (CFS). Warren carved out a wide and deep gorge down to the bedrock that extended from the headwaters to Mankato where an ancient mountain range forced the water northward to what is now the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The Minnesota resides in the bed of the ancient glacial river. Some of that exposed bedrock looms today on the landscape within the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge just south of Ortonville, as well as hidden pockets along the Minnesota River. Friluftsliv, anyone?

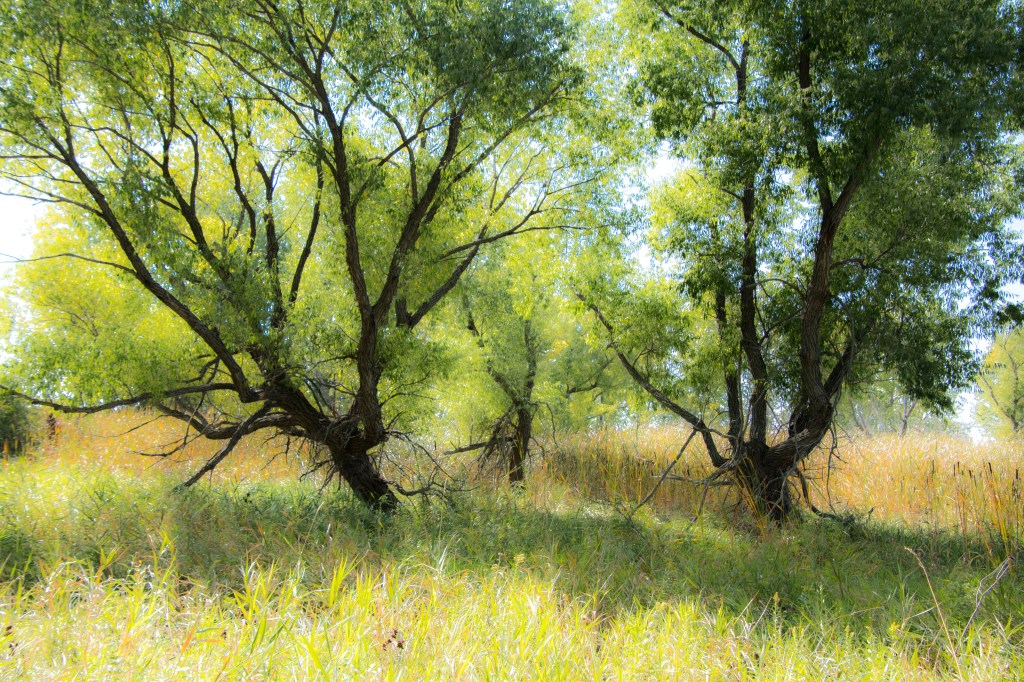

Those “ghosts?” It doesn’t take much of an imagination to recognize where and how many of the huge potholes or lakes existed before ditching and tile draining. Some of that land, like our farm, has been converted back into some restored prairie, perfect for easing into a bit of friluftsliv-friendly sanctuaries.

Also resting in carved bed of the River Warren are two separate areas of Big Stone Lake State Park. The lower Meadowbrook portion is mainly a wide swath of prairieland hosting a healthy stand of prairie grasses and other native flora. Further north is the Bonanza area with both a hillside prairie and a beautiful oak savanna — places you can take a deep breath and find calmness. I frequently practice my forest bathing in the savanna.

We will also make several nature friendly trips over the year to various state parks and NWRs, especially Sherburne and Tamarac. Earlier this week we drove to Sherburne for a last-of-the-year viewing of sandhill cranes. Visually beautiful, and adding to our pleasure was the “music” provided by both countless swans and cranes, accompanied by shrill “sallow flute” piped in by numerous bluejays along the way. Friluftsliv, anyone?

Friluftsliv may be practiced here at Listening Stones as well, for we make several walks a week with Joe Pye through our own restored prairie. Now, in November, golden stems of six foot tall barren Big Bluestem offer us saber-like arches to meander through. In summer numerous species of native flora add color and a haven for pollinators and various bird species. Stopping ever so often, we may watch the frensied flight of a flushed pheasant, or spy goldfinches munching on thistle seeds. Even now, as November lingers, ring-billed gulls glide over the prairie, their feathers gleaming like sparkling silver.

In these trying times, with wars raging in Ukraine, Gaza, Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Libya, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, and Syria (have I forgot any?), along with an extended attempt of a Nazi rising within our own nation, I find a heightened need to seek whatever peace nature seems to offer. A sweet sanctuary for soothing a weary soul. Maybe my baby boy described nature best so many year ago: “Preee …” Indeed. “Friluftsliv” couldn’t have come into my consciousness any sooner.