His email was to invite me to visit his “forest”, adding a tantalizing suggestion of how it would be good for the soul. It was mid-September, back when the days were warmer and the sun seemed to paint most everything with a hint of a golden autumn hue. “It’s in the middle of a section just off the road,” wrote my friend and fellow writer, Brent Olson. While not knowing quite what to expect, it wasn’t going to be Thoreau’s Walden Pond! Different writers, eras and environments, yet a similar need and desire.

Some may know Brent beyond our neck of the prairie. He writes a weekly column called “Independently Speaking” he posts online and to an incredibly large number of subscribers near and far, and he has a growing shelf of books he has written. Seven at last count. Mostly essays with a novel or two wedged within.

When we first met a few decades ago he was giving a reading from his first book at an evening chow feed in the old school in Milan as part of the annual Upper Minnesota River Arts Meander. At the time he was still proudly growing pigs which made him the second hog farmer I knew of at the time to have published a book. I thought briefly that perhaps that was a missing link in my own writing career, that I should be raising pigs. I might add that this was a fleeting thought.

Since I’ve moved into his neighborhood and we’ve become friends, I didn’t take his invitation to his 35-acre cottonwood forest lightly, for I was more than slightly intrigued by both his offer of a walk in the cottonwoods and of soothing the soul. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised Brent had a “forest,” for a few years ago he took issue with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for busily removing trees from their restored prairies in an effort to reduce perching possibilities to hawks and other predatory birds of waterfowl and to restore the land to their long removed heritage.

“I happen to like trees,” came the comment from the avowed prairieman.

While that may sound like a contradiction, it makes Brent sort of a rascal within the premises of the prairie where for many, trees are viewed with about the same reverence as pimples on a teenager’s cheek. His reputation is that of a principled man with a streak of stubbornness, for he seemingly has no fear of paddling against the flow. Making a mark as he’s done for years with both his writing and his community service in committees, organizations and as a Big Stone County commissioner, as a politician he understands the need for a graceful compromise.

His independent nature often forsakes previously agreed upon tracks of “suitable” timing for moving things along. He’s more likely to write a grant to jump differing timetables than convention might suggest, or to take a Bobcat afield to inadvertently build a picnic table from a huge slab of polished quartz he had lifted from a slag pile of a local tombstone manufacturer with grunts and hernia fodder into the bed of his pickup. Once home he headed off into his prairie with the slab and eight angle iron pillars he pilfered from an old grain bin to create a rather sturdy picnic table. That table now anchors what is basically a grassy triangular pheasant haven on the peninsula within a beautiful undrained and shallow 150-acre wetland he calls Olson Lake. “For the pheasant hunters,” he claimed.

Ah, the lake and now a forest? As a third generation owner of the home farm, Brent has followed his family tradition of keeping the shallow wetland intact. On the shores of that “lake” he recently completed the construction of his “writer’s shack” from piecemeal and family relics. It’s a cozy little enclave and wood heated in the winter. Like Thoreau’s cabin, the shack is decidedly basic. By now, perhaps, you’re getting the gist, for his forest, like Olson Lake, stands as a rather defiant metaphor to common acceptance of his prairie peers.

His little forest is located a few miles to the west of the Olson home place. “My forest is the middle of the section,” he explained as we drove toward the dense cottonwood plantation. “Back then when the trees were pretty small I asked Fish and Wildlife if I could keep the trees. They didn’t seem to care back then. Now I’m being told to cut them all down. I won’t. My spirits are always lifted when spending time in here.”

The worn tracks through the cropland surrounding the trees give evidence that his spirits are often lifted.

Many of the cottonwoods are immature, small enough you can encircle the trunks with your two bare hands. Yet, you can almost imagine how his forest will look in 20 to 30 years as competition for light and soil nutrients begin to take charge, crowding out the weaker, smaller trees. Natural succession and selection. Century old cottonwoods around here stretch high into the sky with gnarly limbs towering over competitive species in the dozens of farm groves. Which of the hundreds of cottonwoods that surrounded us within his forest will reach such character and status? All part of time, natural history and mystery. Brent seems content to allow nature to take charge.

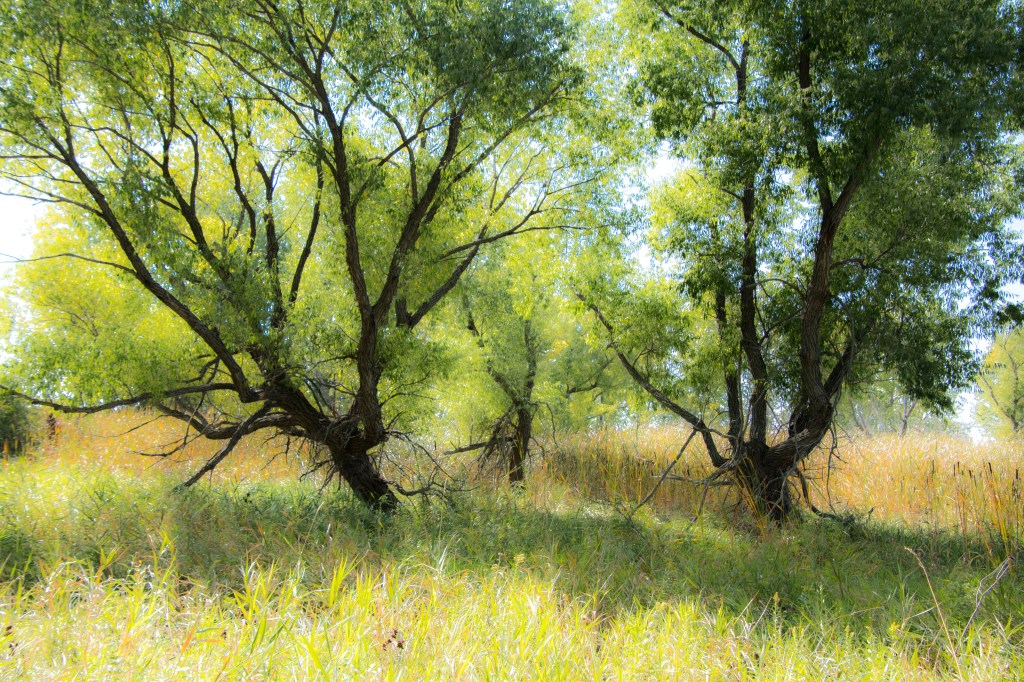

Many of the trees on this beautiful sunny afternoon bore golden leaves, while others held onto a summer greenness making for interesting color contrasts. Intermingled among the cottonwoods were a few picturesque mature willow trees near a small and “dormant” wetland. A bed of cattails gave it away. Despite an ongoing drought, the cattails, willows and cottonwoods left stranded seemed healthy.

His forest, seemingly obstinate in its prairie setting, has a lively and lovely denseness despite the drought, and when in the midst of the timber you are surrounded by such a density of trees the adjacent prairie and cropland cannot be seen. Though we were less than a quarter mile from a county highway, and over a ridge from a major U.S. highway, the trees seem to buffer the outside noise. Thoreau’s wooded enclave? While it’s beautiful with a hillside of oaks and maples alongside a tranquil lake, those triangular woods are surrounded on two sides by multiple lane highways with the third hosting a major bed of commuter and freighter railroad tracks. Outside of his “sleepy” Concord, an incredible imagination is necessary to sense Walden Pond being peaceful and quiet, a haven for the soul.

Here in Brent’s woods you feel a need of taking in a deep, natural breath to allow the surrounding nature to settle into higher sensory levels. Sound, for one, soothed the soul as bird songs joined the soft background music of the shimmering cottonwood leaves. Adding another layer of sensory appreciation was a soft woody scent from the nearby cottonwoods. Not quite apple buttery. A hint, perhaps. As we weaved our way back through the trees toward the pickup, Brent’s “forest” was holding its own here in the midst of an otherwise rather flat and nondescript prairie. He was correct. One’s spirits could be lifted here.