Ah, but the voice sounded vaguely familiar. Something from the past, and for so long so silent, yet, there it was. We were in the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge near dusk with an old friend who I was showing off Minnesota’s two native cacti on one of the flatter outcrops, the brittle prickly pear and the ball cactus, when the sounds of the nearly forgotten voice seemed both clear and so close. Those clear “tsweeeeets” invited me to first look around, then above us where three common nighthawks were casually circling high in the prairie sky.

It had been years, really, since I’ve heard or seen them; so long ago that I could barely remember our last meeting. Yet, here they were, mere miles from my Listening Stones Farm. “Hey, guys. Look up,” I said, pointing upwards toward the birds circling above the prairie grasses. “Nighthawks. Watch them. Pretty soon one will dive so fast and deep you may lose sight of them. They’re one of my favorite moments in nature.”

This I knew from experience due to our last moments of sharing time together, for it was during my years on my second newspaper job in Dubuque, IA., back in the late 1960s. My apartment was on the top floor of an old Federalist building right on the main thoroughfare through the beautiful Mississippi river town, kitty-corner from the public library and just half a block from a funky little jazz piano bar. A deck ran a half block in length, from my back door to the alley, and come spring through the first days of autumn, the deck became sort of a sanctuary where I could lay back with a frosty beer to watch nighthawks circling high above on the river side of the towering limestone bluffs before making one of their characteristic, breath-taking dives. Some claim they can hear a “pop” in the midst of a dive although I can’t substantiate that, not with my hearing.

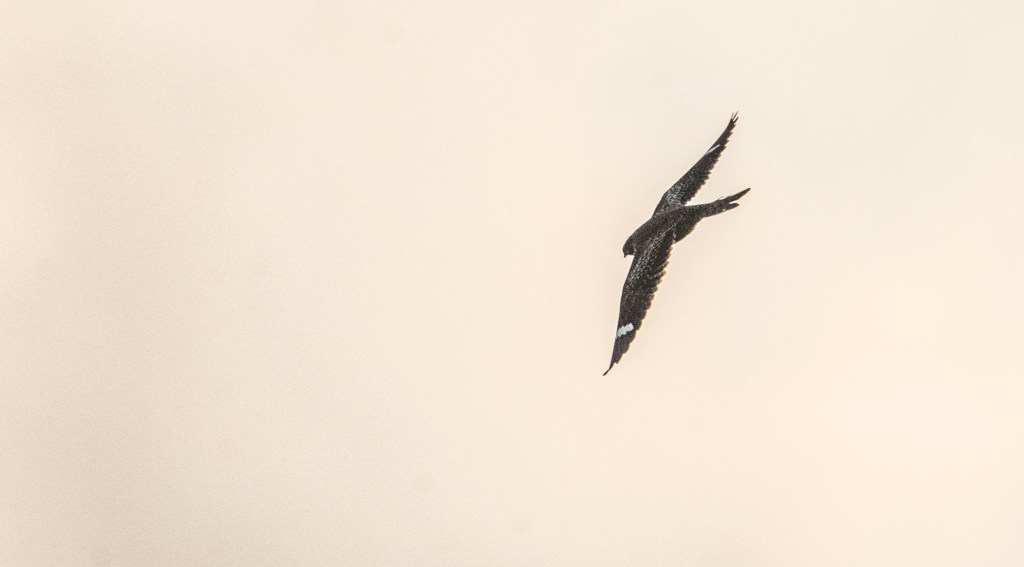

Those dives were fascinating in beauty, and mesmurizing at the same time. In those days the numerous nighthawks plying the sky would hold my interest for many long evenings as I lay on my back to await those blinding dives of hundreds of feet, only to sweep upwards at the last possible second near the rooftops. Yet, there they were, once again gliding seemingly effortlessly high above the outcrops in the evening sky, wings spread wide with those characteristic white wing patches under each wing and the white band across the throat.

Then, as promised, in an instant, one suddenly dove with lightning-like speed toward the ground, sweeping upwards at the last second before it seemed it might bury itself deep into the rock-strewn prairie. According to the guide books, “Chordeliles minor” is called a “common nighthawk,” although thanks to those incredible dives they seem anything but common. Besides being “uncommon,” the birds are neither nocturnal nor hawks. Their closest relatives are actually whip-poorwills and nightjars. Most members of the nightjar family are actual night fliers, yet perhaps the these dusky fliers were muse for Edward Hopper naming his famous lonely nighttime cityscape diner painting, “Nighthawks.”

Once again I found them just as fascinating and mesmurizing on this odd summer night as before. Experience told me there was no possible way to record the beauty of their breath-taking dives with my camera. Not back then. Not now. If not for showing off the seemingly ever present cacti on these flattened outcrops we would have missed them, and those spiney little plants discouraged me from laying on my back once again, hands clasped behind my head, legs crossed, to witness such acrobatic, or perhaps poetic, beauty in flight after some 50 years.

Despite their supposed range that covers most of North American, from the Yukon to the Gulf of Mexico, according to my Edward Brinkley “Field Guide to Birds of North America”, life hasn’t been kind to nighthawks. Studies indicate that their population has decreased some 60 percent since my years in Dubuque. Apparently there are various reasons for their decline, ranging from a move toward a chemical happy mono-cropping of agriculture that has effectively reduced their once abundant insect diet, along with a move from the former tar and gravel rooftops of the old factory and downtown rivertown buildings they used for nesting to the more efficient whitened, reflective roofing. In Dubuque many of those old buildings have since been demolished. Nighthawks used the gravel for nesting and privacy.

According to Gretchen Newberry, who wrote her doctorial thesis on nighthawks while at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, nighthawks are now seemingly only abundant in patchworks of grasslands that have not been farmed, and the Big Stone National Wildlife Refuge, with 11,500 acres of outcrops and prairieland, fits that description.

Indeed, there are seemingly a higher acreage of prairielands along the upper Minnesota River than you’ll find just a heartbeat away from the river as it meanders from Big Stone Lake to the bend northward at Mankato. Newberry wonders if urban nighthawks stumbled into an ecological trap, as roofing materials changed and became unsuitable for nesting. She doesn’t assume that they will find their way back to their natural nesting areas, or even if there are enough of those areas remaining to sustain a sizable population. Gravel patches placed on roofs by kindly naturalists hasn’t worked, either.

So, is our prairies the sustaining answer? With less than a percent of native prairie remaining in Minnesota, and a continued move in neighboring South Dakota to convert grasslands and prairie to cropping land, nighthawks along with numerous other grassland bird species are most likely facing a continued downward trend.

In her study of rooftops, Newberry found that only 10 percert of her studied nests survived from egg to fledgling. Most died as eggs, but many died in the first one to two days of life before they could awkwardly walk to shade. Even adult nighthawks are challenged to walk. Nighthawks are also considered semi-precocial — they’re not as naked at hatching as songbirds are, with those legs are not ready to run like a crane. They’re somewhere in between.

Newberry includes the nighthawks with swallows, swifts and bats as aerial insectivores — animals that fly around most notably at dawn and dusk to forage for insects. “That’s their guild,” she explained in a TED talk, “a group of animals that make their living in a similar way.”

So as we stood next to those rugged flatter outcrops in the refuge, we were perhaps standing in their last sustaining habitat in our prairie region, for the granite and gniess outcrops provide both both camouflage and a flattened areas for nesting — similar, perhaps, to the graveled rooftops along those Mississippi River towns like Dubuque and La Crosse back in the 1960s. And the stagnant old Minnesota River that winds through un-canoeable, log-strewn stretches of water in the refuge seem perfect for those mosquito populations that sustains Newberry’s guild.

Will future generations find the same joy and beauty I have in watching nighthawks lazily soaring in a colorful dusky sky before suddenly making a breath-taking dive for mosquitoes and other available insects? On this evening I found I was just as spellbound in my 70s as I was back in my 20s. I find many reasonable attractions to this beautiful sprawling refuge, and thanks to an unexpected stop to show off a couple of native Minnesota cacti, for one brief evening I reconnected an equally challenged “old friend” so unexpectedly. I couldn’t have been happier! It was, above all, such a sweet remembrance.